KNOW DICK: CHAPTER TEN

HEY! I’M IN AFRICA!!!

Dick Does the Dark Continent, Almost Gets Eaten (Twice) and Stumbles Over Cape Saint Francis (1958 - 1961)

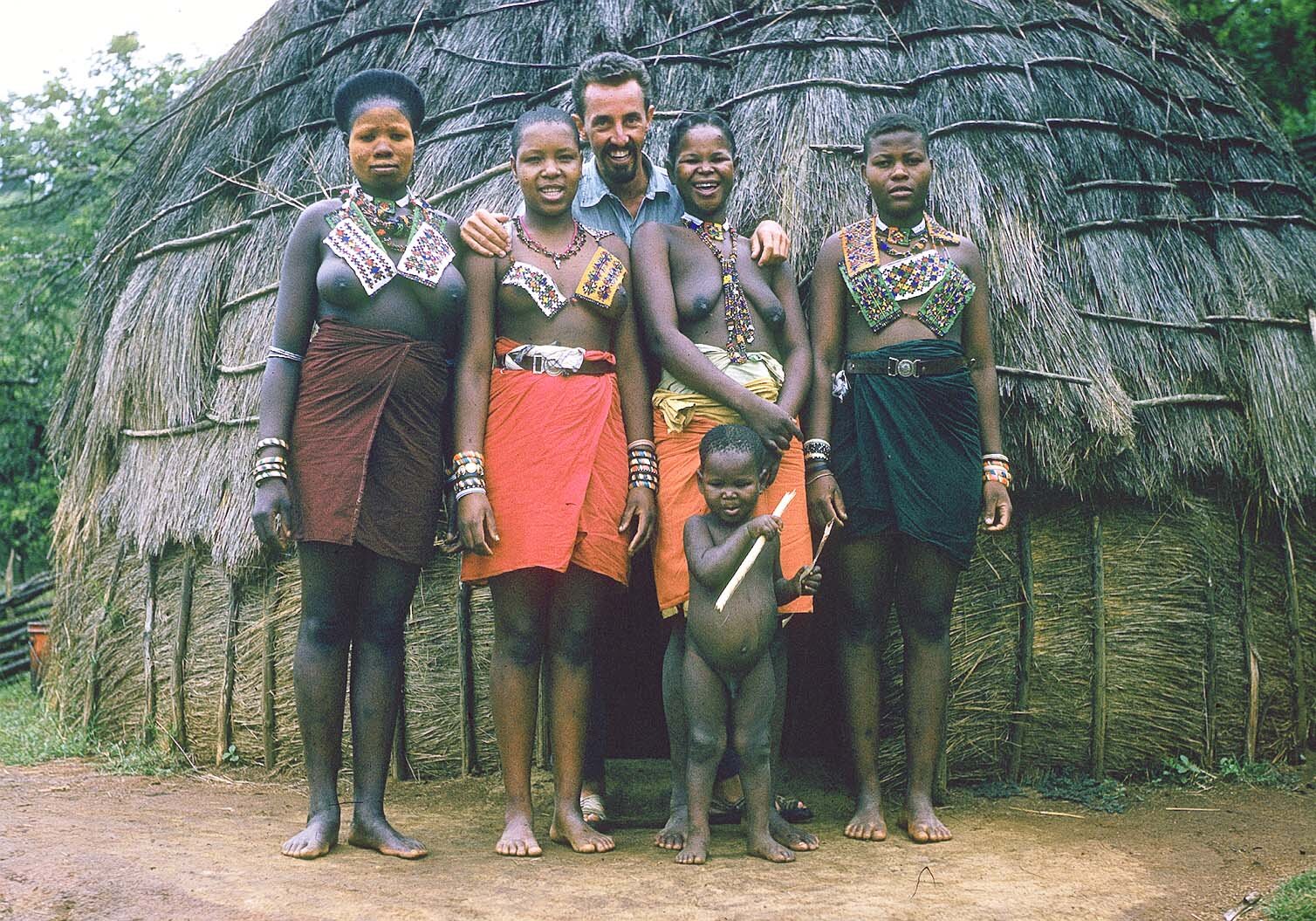

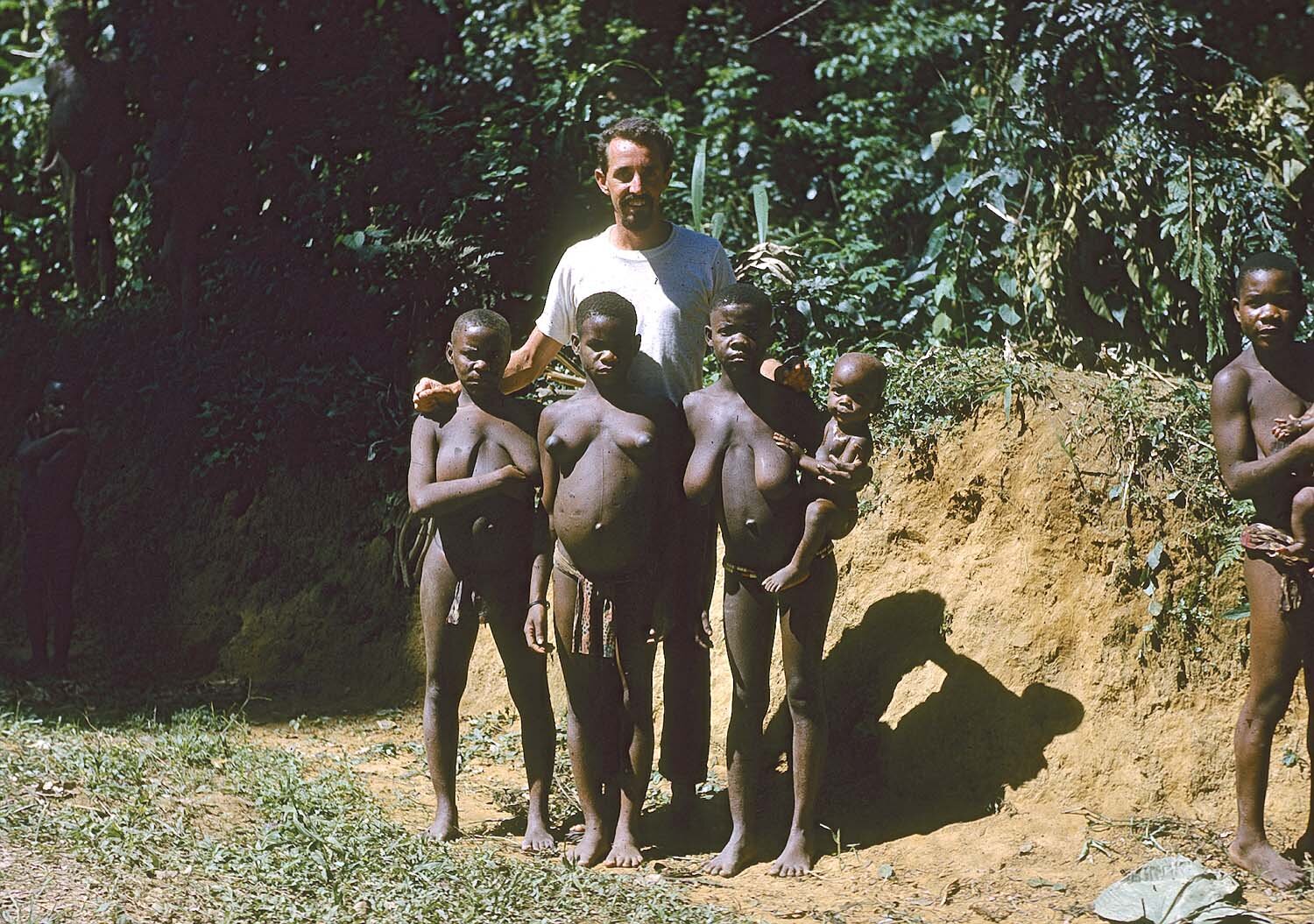

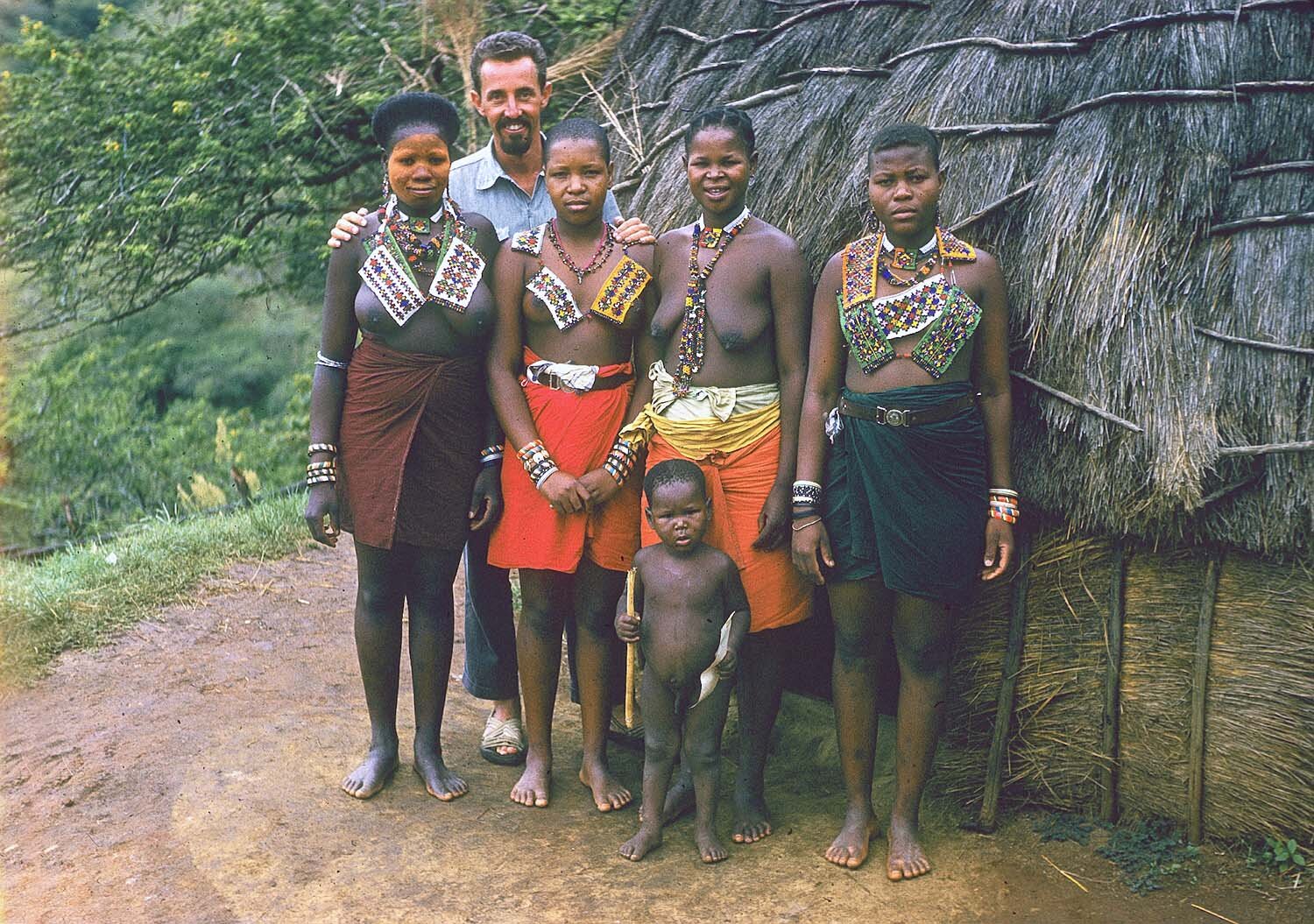

Dick Metz with four of the wives he collected and one of the 25 children he fathered during his time in Africa. Psyche! Just kidding. This is Dick and four Zulu sisters who took him in during a fierce rainstorm in the Zululand section of the Transvaal. Photo: Dick Metz.

Editor’s Note: In 1958, Dick Metz sold a ‘50 Ford convertible for $150 to some friends, and sold the liquor license for the Surf Liquor Store in Huntington Beach to the people building Disneyland. He came out of all that wheeling and dealing with 1958$2100 - the equivalent of $18,900 in 2021 dollars. He sold everything - including his TV - to finance his travel jones.

Dick wanted to see the world and have adventures in places he had read about in Argosy and True and Adventure - men’s adventure magazines: exotic places like Tahiti and India and Africa.

Or so he said.

Truth be known, the 1950s were sexually uptight.

Metz just wanted to meet and/or get laid by wild, non-American, non-1950s, non-morally-conflicted women who weren’t afraid of having sex/getting pregnant.

But if anyone had asked him what he wanted, Metz’ Do It list had five major goals:

Go to Tahiti and see bare-breasted women.

Surf in Australia. He knew there had to be surf there.

Go to Africa and see wild animals and tribes.

Attend the Olympic Games in Rome for 1960.

Run with the bulls in Pamplona, Spain

He did all that and so much more.

From 1958 to 1961, Dick Metz left California and traveled around the world the old-fashioned way: From California he jumped trains and hitched through Mexico to the Canal Zone in Panama, where he paid 1958$60 for a seventeen-day fare from Panama to Tahiti [2021$526.83]. There was no commercial way to get to Tahiti back then so he caught a ride on a troop ship with a mob of burly French Foreign Legionnaires who were headed for Vietnam and that whole mess.

He did indeed see bare-breasted women in Tahiti - one of whom sucked on a fish head in bed and then waited, topless and covered with scales and guts - for Dick to make a move.

After adventures in Tahiti he jumped freighters and passed through Apia, Pago Pago, New Hebrides, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tonga and then landed in Newcastle, Australia.

Dick Metz, socializing with a stylish island friend in the Society Islands. And a side note: Look at how clean and crisp these photos are. They’re 62 years old, and they’re perfect. Kodachrome, brings out the nice, bright colors…. Photo courtesy Dick Metz.

From Australia Dick jumped more freighters and passed through Indonesia, Singapore, Bangkok, Penang, Kuala Lumpur, Rangoon, Calcutta to New Delhi and then Bombay, where he paid $10 for passage on a ship called The State of Bombay - a poor ship taking poor Indian laborers to Mombasa in Kenya: “to work on roads and stuff.”

The SS State of Bombay which Metz took from Bombay to Mombasa. Can’t find any information on length, speed, etc. for some reason. But they made it.

For 1959$10, the equivalent of 2021$90, Dick passed through the Seychelles Islands and Zanzibar before setting foot in Africa for more adventures.

Dick had a thousand adventures and survived them all. This excerpt details the “discovery” of Cape Saint Francis by an outsider, and how almost getting eaten by lions and leopards and bare-breasted women lead to Dick not getting out of the car in pitch black midnight at Victoria Falls and how that lead to the famous perfect wave scene in The Endless Summer.

Below is one 19,000-word chapter from a much-longer, 90,000+ word “webiography” of Dick Metz -interviews by Tim Delavega and edited by Margery L. Schwartz and Ben Marcus.

Color by Kodachrome. This will be even better when we get all of Dick’s visuals.

Mike Hynson, stoked and disbelieving and suffering a good case of the bends at Cape Saint Francis, from The Endless Summer. Frame grab from the movie.

THERE IS CAPE SAINT FRANCIS DNA IN KELLY SLATER’S SURF RANCH

The best laid plans…. Dick laid down his intentions to a local Laguna Beach newspaper. Some of them came true, some didn’t. But he did go around the world.

INDIA TO AFRICA FOR $12: CABIN CLASS

How was that sea “leg”?

I was supposed to be sleeping on the deck with all the Indians. But because I’d been to sea before, I knew how it worked. I knew that all these ships had some private quarters, because they need to isolate sick people, so everybody else doesn’t catch whatever disease they have. So there are always cabins that they keep empty to put anybody who gets sick. I could see that on this ship, right on the fantail, there were several rooms, cabins up there, that nobody was allowed to get to. The captain was British, and there were a lot of Indian crew, but there was also some British crew. So the first day on board, I just laid my gear down on the deck and went up to one of the British sailors, and said, “Hey, how can I get in that isolation room up there on the fantail?” And he said, “It’s no big deal, nobody’s using it, there’s nobody sick, so have at it.” So I just kind of conned my way up there, and I had a room—you know, a cabin—to myself for the next, I think it was, twelve days going across the Indian Ocean. It worked out really well. I’d sit up there and eat the rice and curry you’d buy on the ship. There was no dining hall. You’d just buy it and go sit on the deck and eat it. I was a deck above and could see all the Indians where I would’ve been, on the normal deck, and they were in the hold too. But I had this nice, sunny, private little area for the whole time.

HE SAILS TO THE SEYCHELLES

The first place we went was the Seychelles Islands, which are in the middle of the Indian Ocean - Mahe is the main city. It was just like in Tahiti, because there had been Arab Dhows from the Arabian Peninsula that had come to Africa, and with the winds, they’d stop in the Seychelles. At one time it had been a French colony, then a British colony, so you had French and British white people mixing with Arabs and Africans, and god, they looked just like Tahitians. They were light-skinned with beautiful features. And the Seychelles were extremely beautiful too—white, sandy beaches. There’s surf there. Diving was spectacular. But we were only offloading, so I was there maybe three days. I was just really impressed with the Seychelles. They were really spectacular. And I had a great time. I went to a bar the first night there, and they had an old-fashioned jukebox with 78 records, and they were playing, over and over, Glenn Miller, “In the Mood.” They just kept playing it and playing it. I was dancing with all the gals there, and it just reminded me of Tahiti, because they were all drinking and partying and having great fun.

ZANZIBAR

We went from the Seychelles to Zanzibar, and I think we spent a day or two there, again offloading. That’s where the great slave trade took place. The Arabs would come to Africa, East Africa, kidnap the blacks, take them to Zanzibar, and auction them off to be shipped all over the world. Primarily to the Arab countries and to Europe, not to America. Our slaves came from West Africa, not East Africa. Zanzibar is called the Spice Island, and as soon as you get close to the island, you could just smell it. It smelled of cinnamon and cloves and all kinds of neat spices. It’s close to the equator and has beautiful weather and warm water; it was pretty neat. So a day or two there, and then it was only another day’s voyage to Mombasa, where I got off.

INTO AFRICA - THE CONTINENT

When you finally got to Mombasa, what were your plans?

That’s when I started hitchhiking all over Africa. I had my visa for Kenya. You’re at sea level at Mombasa, you’re right at the equator, and you go up to a plateau, it’s about 5,000 feet high. I got a ride, and the guy I was riding with said, “I’ve gotta stop and see a friend, would you like to meet him?” And it was the most famous hunter in all of Africa. I think his first name was John, but I know his last name was Hunter. He wrote a book called Hunter - by J.A. Hunter. He was a Scotsman and among his exploits he was hired by the British government to shoot the lions that were eating all the Chinese workers.

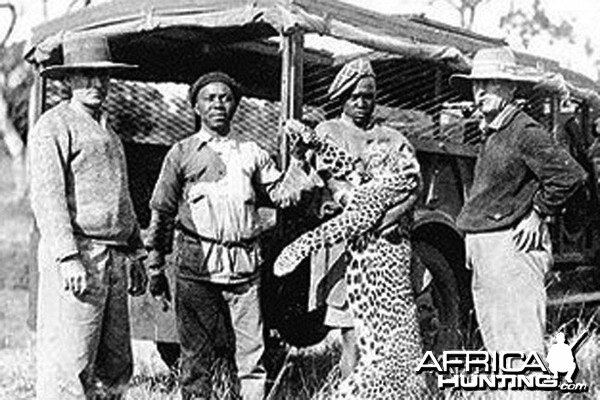

J.A. Hunter (left) and his trackers and clients with a very fine Leopard. From www.africahunting.com/threads/john-alexander-white-hunter.3120/

The guy invited us for dinner, and he told us they were constructing the railroad from Mombasa up to Nairobi, and they had a lot of Chinese laborers. Well, the lions were killing the laborers, so they hired Hunter to kill the lions that were marauding their worker bees. He had Rhodesian Ridgebacks—the ones I’ve seen here are usually like eighty or ninety pounds—those guys weighed 150 pounds and were like three feet tall. They were more like Great Danes than they were the Ridgebacks I’ve seen around here. They were huge, big things, and god, they were really fast and meaner than hell. That was the first time I’d ever seen a Rhodesian Ridgeback that big and fierce, and Hunter was telling us at dinner how he’d shot all these lions. There were stuffed lions heads around the dinner table. But he was really a neat guy. I told him that I was just hitchhiking around. He asked me a bunch of questions, and I told him I wanted to see Africa and to work there, so he gave me the name of a safari company in Nairobi that he had worked with.

NAIROBI

A couple days later, when I got to Nairobi, I called the company and got a job—well, it wasn’t right away. I stayed at the YMCA for a couple of nights, and then I got a job with this safari company that was taking guys on photographic safaris—not on hunting safaris, because at that time they had started trying to save the big game. So I worked on a safari team, and we would go out in a couple of big English Bedford trucks and set up the tents and mess hall and little heads and all that stuff. There were a couple of white hunters from England who lived in Kenya, and they would take people out. I’d go in the jeep with them. I really lucked out…. Anyway, the steering wheel was on the opposite side [of what we have here], and the exhaust stuck out high above the roof because you’ve gotta ford a lot of streams. They’re a lot more rugged than the ones that you see around Newport Beach. I wouldn’t have had the chance to get out on these safaris if it hadn’t been for that job. They really didn’t pay anything, but you got room and board and I got to travel—we would get up real early in the morning, in the dark of night at four, and go out to different salt licks that they, the white hunters, knew of. And we’d set up photography camps.

THE CROWN SCENE AT TREETOPS WITH THE QUEEN AND ELEPHANT

MAASAI MARA AND TREETOPS

I worked maybe three weeks for those guys, and went to all the major parks—Maasai Mara National Reserve and Treetops, which is up by Mount Kenya, and stayed in that. It’s a huge, big tree that people spend the night in. There’s some water right below it, and animals—elephants and lions and all kinds—come there to drink at night. They kind of watched each other, because they were all drinking out of the same hole. You’re up in this tree house, and god, it was really neat. You got a different perspective. But it was really costly. I never would have been able to go there if it weren’t for working on the safari.

AFRICAN WILDLIFE: A SLIDESHOW

SERENGETI’S GOT GAME

We also went over to the Serengeti. We got pictures of thousands and thousands of wildebeests crossing the Serengeti, and the crocodiles and the lions chasing them. It really is a movie out there, and just spectacular scenery. It was much more than I ever expected to see in Africa. The sheer number of the game; it was really unbelievable.

OUT OF AFRICA FIRE AT THE KENYA COFFEE PLANTATION

I wanted to go to different places. At Mount Kenya, there was a lot of coffee growing. In the movie Out of Africa with Robert Redford and Meryl Streep playing Karen Blixen—anyway, that’s where they were, up on Mount Kenya on a coffee plantation. So I went up there. The story was that she was from Denmark, the real gal, and came to East Africa and fell in love with a white hunter (played by Redford). I had read a bunch of books and seen different movies—another was Born Free, about raising baby lions and then training them to go back out into the bush after they’ve been raised by civilians. That was another great book. So having read those books and seeing the movies, when I was there, seeing it all for myself—the game, the scenery… it was just spectacular and really interesting.

TO THE END OF THE PAVEMENT

How long were you out there?

Eventually, after about three weeks, I went back to Nairobi. And once I got back there, I just started hitchhiking. I wanted to go back out into the woods. You know, it’s not like hitchhiking around here. It’s paved all around Nairobi, just like any city. But as soon as you go two miles out of town, the paved road turns into dirt, and the dirt road turns into a track, and you’re in four-wheel drive. We would drive for maybe six, seven hours and only go 100 miles. It felt like you were just winding around out in the weeds. So people didn’t just go out touring around. And the people I would get rides with, usually only went to the end of the pavement; that’s about as far as anybody went.

An African superhighway, circa 1959.This is where Land Rovers are life and death, and why they are built so well. Photo: Dick Metz.

There were English kids—I say kids, but after they’d graduated from college with a degree in Geology, they would get a job with De Beers mining company. De Beers would send these young guys in groups of about four to pan just about every little creek to see what kind of minerals were in there. They’d set up camp and work in a spot for a week and then take down the camp and drive maybe fifty miles to another creek and set up camp all over again. So I got rides with these guys who worked for De Beers, because they were the only ones out there in the bush. Every now and then, a white hunter would be out there with a client on a photography expedition, and I would get a ride with them. But they were never going anywhere. It’s not like you’re going from one town to the next.

In the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion eats a zebra.

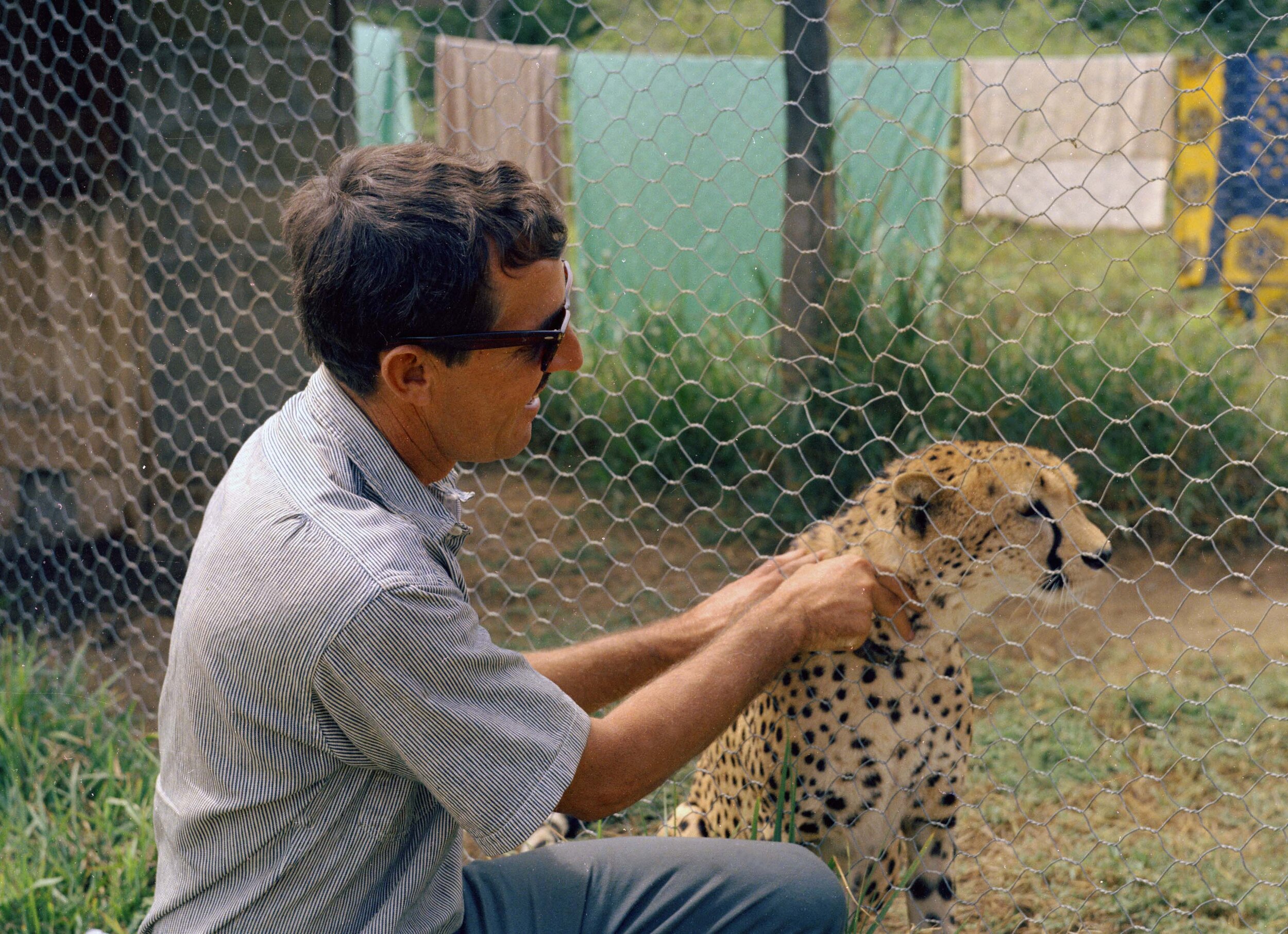

DON’T SLEEP IN THE SERENGETI, DARLING

A couple times, when they were heading off in a different direction, I got out of the car and slept out in the Serengeti by myself. One night I slept out, and it was scary being out there by yourself, hearing the lions and animals in the distance. I was right by this dirt track in case somebody came by. In the morning, when I got up, there was this little mound hill, so I walked over to it, and there were two male lions lying in the track, sunning themselves. They’d obviously just eaten something. Once they’ve had their fill, you know, they’re not very aggressive. Fortunately for me, they were just lying there, and they could tell that I was there, smell me and see me. But they didn’t get up; they didn’t make any moves. I was by these acacia trees. The plains are pretty grassy, with acacia trees scattered around. So I just stood by that acacia tree and figured if nobody came by, I’d be able to climb that tree. Lions don’t usually climb trees like leopards and cheetahs. They didn’t bother me, but they scared the hell out of me. Here they were sleeping about fifty yards away from where I was sleeping. They could’ve eaten me and I wouldn’t have even known it. I sat out there for four or five hours. Finally, a geologist came by, and he was going into Nairobi, so I went back there with him. Being out in the plains with many game, just seeing them in their natural setting and being there, you’re so vulnerable. It was just scary as hell.

It reminds me of surfing when I first went to Hawaii. You know, you go out to Sunset or Waimea or Makaha on a big day, and it keeps getting bigger and bigger. And at least when we first went over there, we didn’t have the right boards. Nobody had the right boards. You couldn’t really make the wave, but you had to get in. I remember a dozen times when I’d say - I’m not a very religious guy - but I’d just say, God, just let me get to the beach. I won’t come out again, I promise. And you finally get a wave and get in, and it’s so bitchin’ that you turn around and paddle back out, and say, Just one more. I had that same sense when I was out in Africa. I said, God, just let me get back to Nairobi, to the YMCA, and I won’t come out here again. But it was just so thrilling and scary, that, at least to me, having this wild adventure that you never thought you’d have, all of your senses are heightened. It’s great, but once you get in a car or get back to city, you’re like, God, what a relief. It was exciting, but you’re not too anxious to do it again.

THE NAIROBI TRIO (ASK YOUR GRANDPARENTS)

So I hung around Nairobi and went out on different trips in different ways. I’d get a ride with a truck driver who would be going up to another city, maybe a three-day ride, and then come back to Nairobi. That way, I just got to see the country. And when I was in a major city, on rainier days or days I didn’t have anything to do, I’d go to the library and read reference books. I really didn’t learn much geography or history at school. But when you’re there, right in the middle of it, it’s really fun to learn about it, because you’re living it. So I’d read all these books and decided on the next place I wanted to see in Africa. I learned about Tanganyika, which is now Tanzania, and Dar es Salaam, which was the capital. So many great-sounding names. I started to lay out a course of where I wanted to go.

TANGANYIKA

Once I left Nairobi, I decided to go to Tanganyika, and to the town of Arusha. I spent the night there. Usually what I’d do when hitchhiking was, I’d spend the night in a little African town that had, usually, a police station, which was just a straw hut and a couple of African supposed-policemen, but they were never trained; they were just guys who had a hat or a badge or a shirt or something that gave them a little authority. I had a blanket with me, and I’d lie down in front of the police station, sleep right there by the front door. So if anything happened, I felt safer by the police station. I don’t know why, but nothing ever happened. I did that a lot, and it seemed to work pretty well. I went to different places and would, of course, try to get something to eat, buy some food where all the Africans were eating, because there weren’t any hotels.

Up close and personal with a wild African baboon. Photo: Metz.

MONKEYS AND GORILLAS AND ELEPHANTS AND RHINOS - OH MY

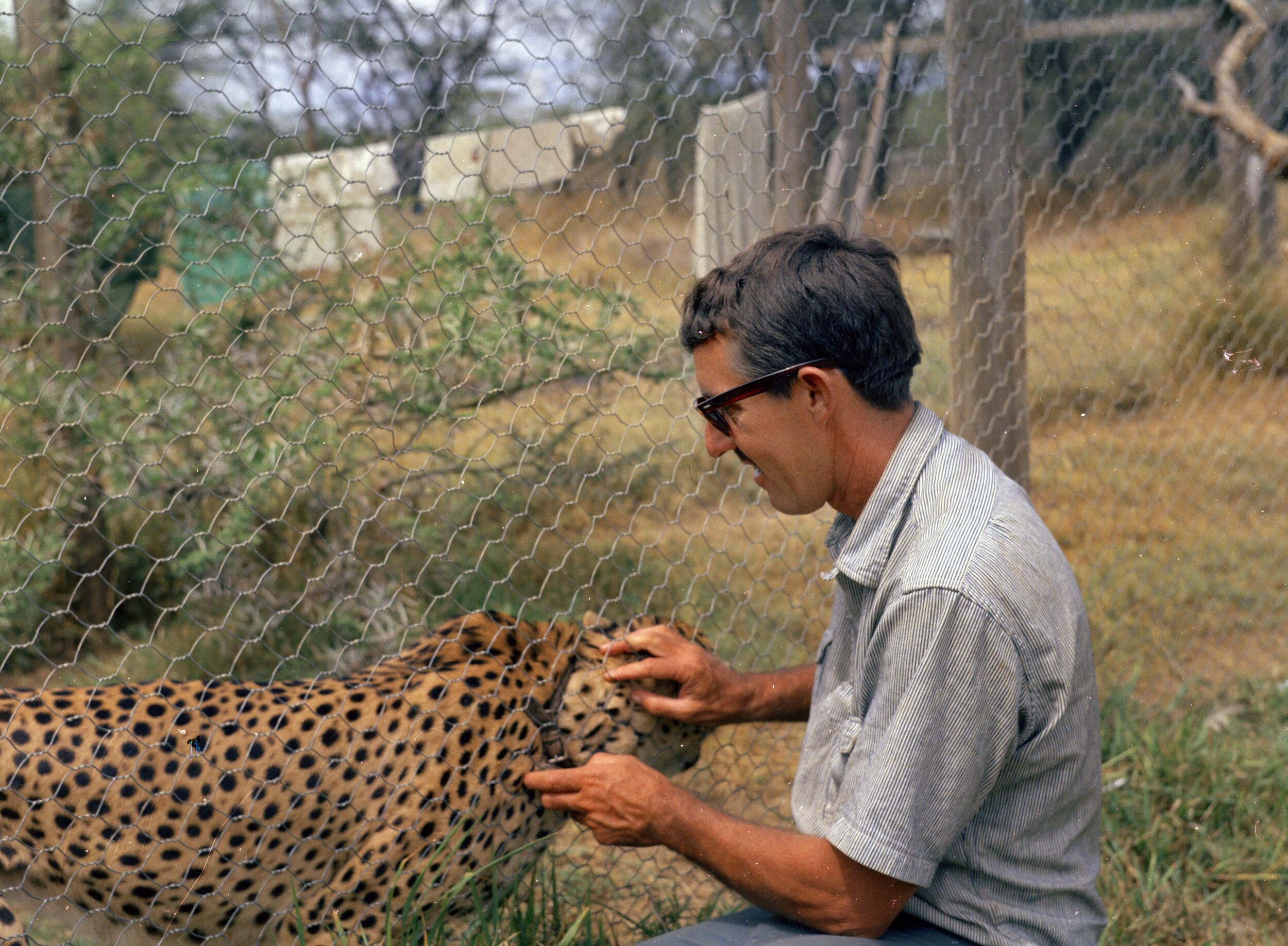

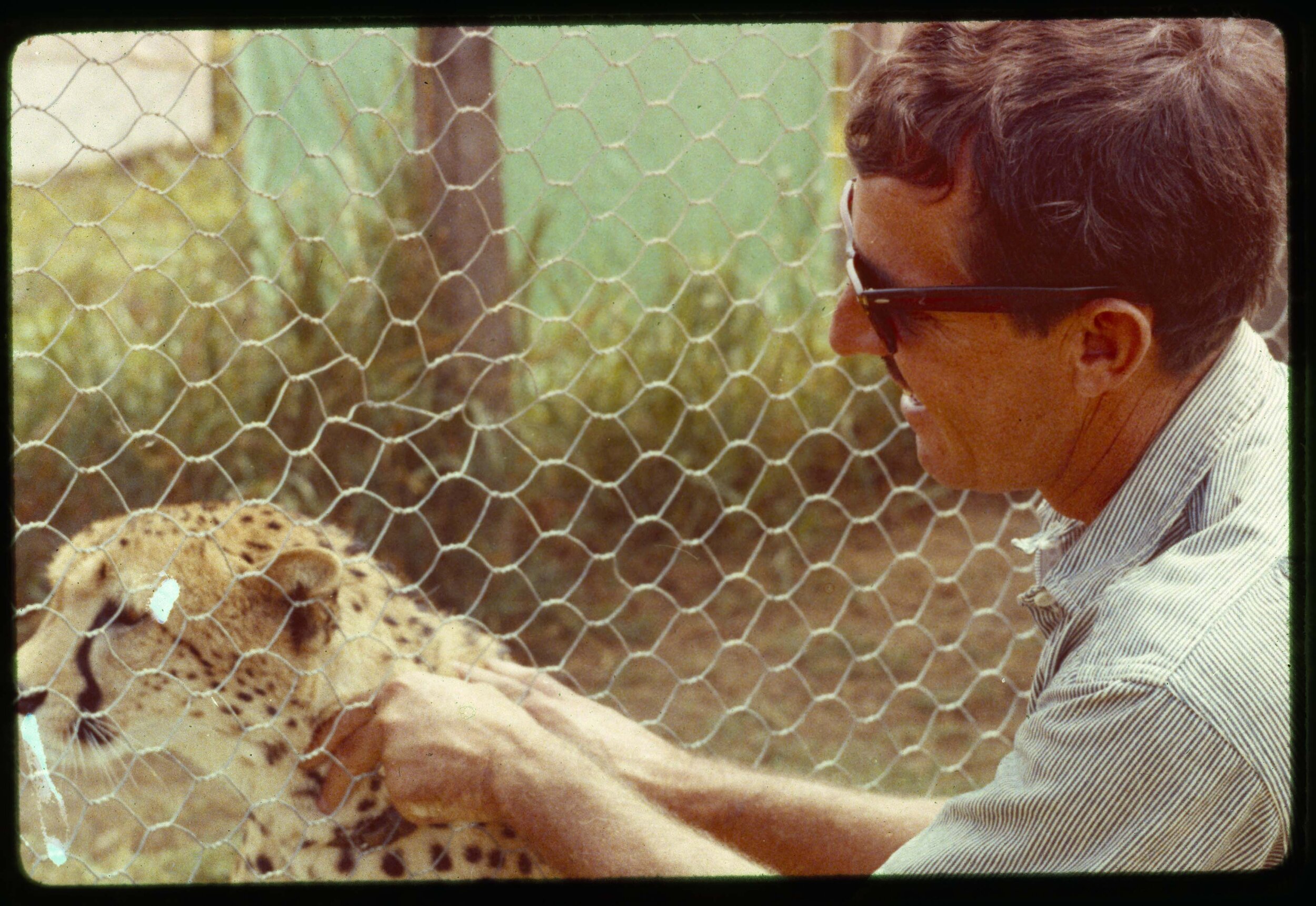

I decided I wanted to go to Mount Kilimanjaro, on the border of Kenya and Tanganyika, and Mount Meru, which is a sister mountain to it, not quite as high. It was suggested to me that I go up to this German ranch, this farm up there. They were supposed to be really nice people and they spoke English. I was told that I had to go up there and see the rhinos. Different elevations and different types of country were home to different animals. You don’t see elephants so much out on the Serengeti plains. That’s more antelope-type animals—and lions chasing them—buffalo, wildebeests, all those kinds of animals. In the jungles you’d get more monkeys and gorillas and elephants and rhinos. So I got a ride out to where this German farm was, and hiked up a dirt road to the ranch house. The people were really nice, and said that I could stay if I wanted to work. I said yeah, absolutely, and she said, this German lady, that they would give me room and board if I helped out on the ranch. They lived in the saddle of Kilimanjaro, which is over 19,000 feet high, and Mount Meru, which is like 15,000. They also were right on the equator, but because it was so high, it wasn’t really hot and sticky. It was warm, but not humidity warm like when you’re in Singapore, right at ocean level on the equator. The temperature was great. I slept in the back sort of washroom in their little farmhouse. They just had one bedroom, and we ate in there. They didn’t have any panes of glass on the windows, which were about seven feet high. I couldn’t look out of them; they were over my head. But they let in light and fresh air. There was also a storeroom, about eight feet square, where their two big Belgian Shepherds, black and brown, usually slept [Ed. Note. The dog that accompanied the Navy SEALs on the bin Laden raid was a Belgian Malinois]. I have several pictures of me playing with them on the front porch. They were really big and good dogs, and they were also great watchdogs - up to a point.

A LEOPARD GETS PAYBACK

CAT’S REVENGE

I’d been there three or four days, when one night, I’m asleep and, not hearing a thing, a leopard came in through a little window—about a two-by-two-foot opening with no glass on it—into the room where the two dogs were sleeping. I didn’t hear a peep out of them, but the leopard came in and killed both of them, and then took them both out that little window. The next morning we found what was left of their carcasses about forty to fifty feet from the house. That leopard certainly just as easily could have come in the same window, or one just like it where I was sleeping, and carry me out. Over a period of time, I learned how scary it was out there, and how aggressive those animals can be. But at that time it just enticed my curiosity, and I wanted to see more.

Two dogs for every boy. These are not the Belgian Malinois eaten by the leopards. Malinois are gnarlier than this. It was a Belgian Malinois that accompanied SEAL Team 6 on the bin Laden raid.

LET SLEEPING RHINOS LIE

One of the days when I wasn’t working on the ranch, I asked where I could see some rhinos. I was told that there was a bunch of them up the hill a couple miles. There was an African native who was hanging out there at the ranch. He was hired by the government for pennies a day—they got nothing, because they were young, probably twenty years old, native African guys. They were paying him to watch and count the herds and keep track of where they migrated to. He didn’t really count all the antelope, but if there were rhinos or bigger game, he had a little notebook and he’d mark down what he’d seen that day. So I walked with him three or four miles up the slope of Mount Kilimanjaro. He was checking out a herd and said, “Actually, I think I see one over there.” So we walked another couple hundred yards, and there was this rhino lying in the dust sleeping. There were a few bushes around, so I didn’t see him at first. We got within maybe 100 yards of him, and the guy said that he’ll probably just continue sleeping and wouldn’t bother me. So he went off to watch some of the game, and I had my camera, of course, and I walked about another twenty feet up behind the rhino. He still didn’t stir, so I took a picture of him laying there. Then I kept approaching him, up another twenty or thirty feet, a little closer and a little closer, and I took a few pictures of him—he didn’t move. He was just sleeping in the sun; it was the middle of the day. There weren’t any big trees around, but there were these acacia trees out there, so I picked one that I figured I could run to—you know, I ran track and was pretty fast, so I was cocky about being able to outrun a rhino. I wanted to get a picture of this rhino standing up, so I got within about thirty, forty feet of him, and I picked up a rock and threw it at him. It hit him on the hip, as he was lying down. Of course that woke him up, and he jumped up and was facing the other way. But I could tell he was sniffing the air. I took a picture of him, and then he started pawing at the dirt. He got my scent, turned around, and I got a good head-on picture of him. Then he just charged, and I ran as fast as I could to that acacia tree. He was probably gaining on me. I don’t know, I wasn’t looking back, but by the time I got up to the first branch, he smacked the tree. I could only get up seven or eight feet or so. It was a little tree, and the rhino knocked it over. But it went over slowly, gradually, because he didn’t take it out by the roots. I was down in the branches and I thought, Oh shit, what’s he gonna do now? He just pawed the dirt and trotted off. Anyway, that was my close encounter with a rhino, and I did get a great rhino shot.

Mount Kilimanjaro overlooks a mob of zebras. Photo: Metz.

Just about every day I was out there, especially by myself and not in a car, it was exciting to get really close to the game. I have a bunch of pictures of a lion that had just killed a zebra, and I touched him. I was two feet away from him. They only eat about every three days, so once they’ve eaten their fill, they just kind of nap in the sun and relax, so they’re pretty harmless then. I was in the back of a Land Rover, and got some great pictures with these white hunters. I remember going back to the farm that night and telling the couple about my escapades. All around the house they had these monkeys, but they were really grieving over losing their two dogs that were taken by that leopard.

Still life with zebra, overlooking Nogorongoro Crater. Photo: Dick Metz.

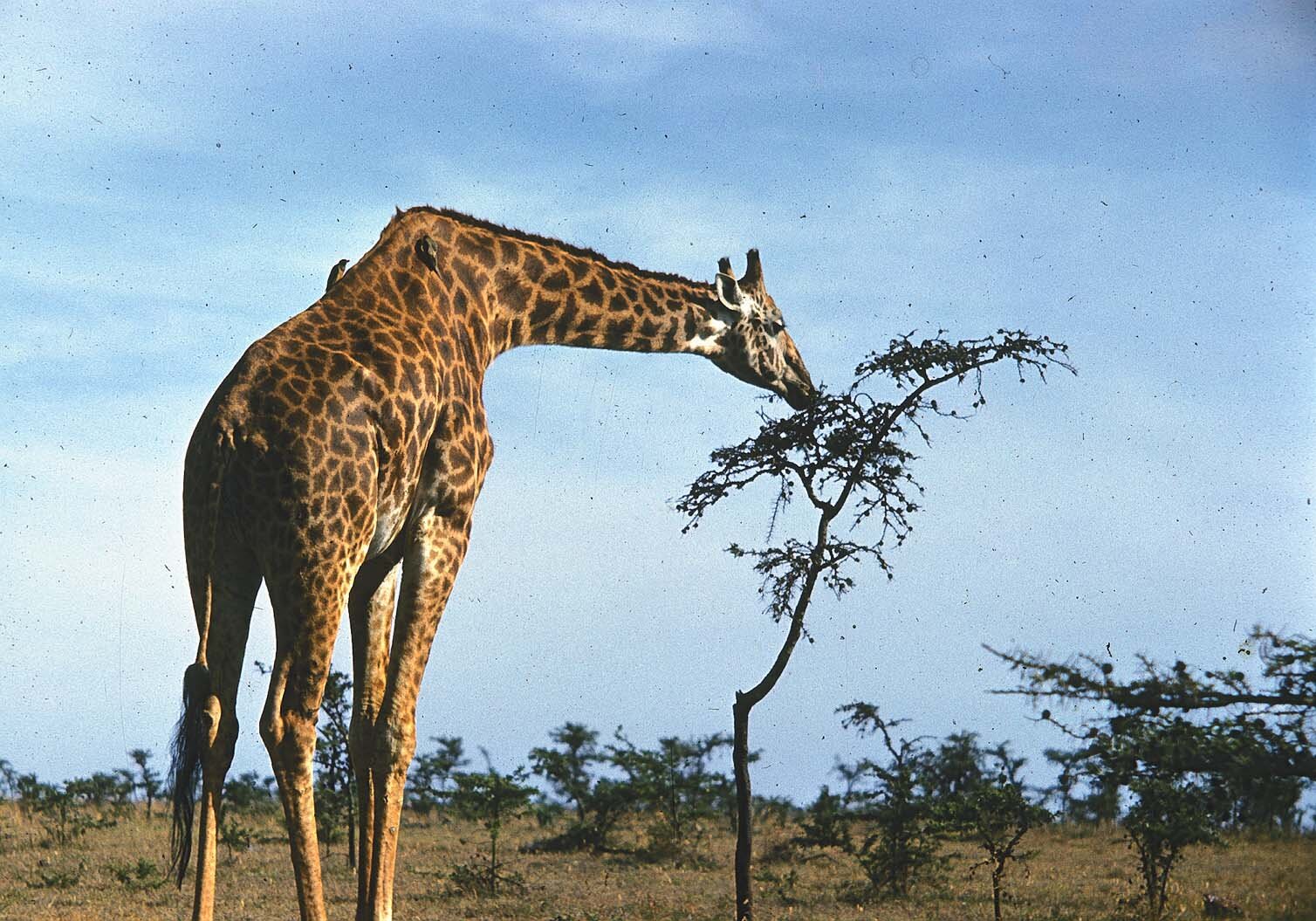

A few days later, I hitchhiked back to Arusha, and spent the night there. The next day I got a ride with a couple of tourists who were with a white hunter. Usually a wealthy guy and his family would hire a white hunter in a Land Rover to take them where they could find game. And I found that they would stop for me because it was so rare to see someone hitchhiking. I usually had an American flag on my rucksack, and they’d ask me what the hell I was doing out there, and where I was going. I’d learned about the Ngorongoro Crater, this gigantic extinct volcano. Twelve miles across, it’s just an empty volcano crater, all the lava long gone. There’s water in the bottom of it, and fertile ground and grass all over. And inside this crater, there’s all kinds of game. They can get out and come back in, but it’s a hike. They’ve gotta hike up the edge of the thing. There’s so much food and water inside the crater, I think that once they’re in there, there’s no reason for them to leave. You can’t hunt in there, so it’s just spectacular. There were a couple of hotels, or lodges, on the rim, but not big high-rise hotels. They were single story, with maybe fifty or 100 rooms each. And there’s a dirt road that goes down from the edge of the crater where the hotels are, so you can ride down inside, to the base of the crater, and that’s where I saw a pride of lions killing a zebra. You know, it’s the females who kill the other animals, and then the male trots up and scares the females away, and he gets to eat all the good parts before he lets the cubs and the females have theirs. I got some really great up-close pictures, being able to ride within the Land Rovers. I spent about a week around the Ngorongoro Crater, and really got my fill of animals—giraffes and rhinos and elephants and Cape buffalo.

Hyena in plain sight, from within Ngorongoro Crater. Photo: Metz.

The next day I started hitchhiking again from Arusha—it’s kind of a little junction there, where the road going to Nairobi comes together with the Dar es Salaam road, and the beginning of what they call the Great North Road. Africa is four times larger than the United States. A ride from Laguna Beach to New York is like a five-day drive, if you drive every day, all day long. Well, if you go from Nairobi to Cape Town, it’s like three times as far. And this was through the jungle, which, of course, is a lot rougher going. No freeways. So a guy came by—a Danish guy—in a four-wheel drive vehicle. He stopped and asked me where I wanted to go; I told him Victoria Falls. That’s in the north, on the border of northern Rhodesia and southern Rhodesia [now Zambia and Zimbabwe] on the Zambezi River. He said, “Great, I’m going right through there, get in.” So I jumped in, and he said, “My mom is really sick in Cape Town in the hospital, and I’m driving straight through, and you can help me drive. We’ll drive two-hour shifts. You drive for two hours, then you can sleep and I’ll drive for two hours.”

So we traded off and drove for, I don’t know, like three days off and on. Before I’d leave any little town we passed through, I’d buy a big jar of peanut butter, and three or four loaves of French bread, you know, long, skinny bread, and put it in my rucksack, because it didn’t spoil. The one crop that’s grown all over Africa is peanuts. They’ve got peanuts everywhere—and peanut butter. So I always had something to eat. But it was always peanut butter on that French bread. Pretty good, but you get tired of it, three meals a day. The guy had some food—there’s not much out there—and you had to carry cans of gas. There were little villages, but no gas stations or hotels or restaurants. And you’re just bumpin’ along. Occasionally there’s a little town that would have a general store, and you could buy a couple canned goods and stuff. So for three or four days, we drove from Arusha across Tanganyika and into the Rhodesias. Finally, in the middle of the night—he was driving—he wakes me up. I was sound asleep, and he said, “Well, here we are at Victoria Falls. That’s where you wanted to get out.” I looked out the window, it’s one in the morning, there were a couple of fires and two or three little huts like there are in all these little villages. Of course, no lights, nobody around, no buildings of any kind, just little huts.

I said to him, “I forget, where did you tell me you were going?” And he said, “I’m going to Cape Town.” And I said, “That’s on the beach coast, isn’t it?” And he said, “Yeah. It’s the tip of Africa.” And I said, “Screw it, I can see Victoria Falls later. I’ll go with you to Cape Town.”

Victoria Falls. No this photo was not taken by Jeff “The Rainbow Man” Divine. It was taken by Dick Metz when he returned to Victoria Falls in the daytime.

If we had arrived in the middle of the day, I might have got out and stayed and not gone to Cape Town - and Mike and Robert might not have scored perfect Cape Saint Francis in the Endless Summer. It’s funny the way the ball bounces. That particular moment was the key decision that changed the lives of tens of thousands of people in the surfing world.

I said to him, “I forget, where did you tell me you were going?” And he said, “I’m going to Cape Town.” And I said, “That’s on the beach coast, isn’t it?” And he said, “Yeah. It’s the tip of Africa.” And I said, “Screw it, I can see Victoria Falls later. I’ll go with you to Cape Town.”

If we had arrived in the middle of the day, I might have got out and stayed and not gone to Cape Town - and Mike and Robert might not have scored perfect Cape Saint Francis in the Endless Summer. It’s funny the way the ball bounces. That particular moment was the key decision that changed the lives of tens of thousands of people in the surfing world.

Victoria Falls - aka in Lozi as Mosi-oa-Tunya = "The Smoke That Thunders" and in Tonga as Shungu Namutitima = "Boiling Water"). First seen by the white eyes of David Livingstone in 1855. Photo: Metz.

FATE RIDES SHOTGUN

I was with that guy for seventeen days. He was a nice guy, and fortunately the trading-off driving and the car worked pretty good. When we got to Cape Town—a big port city in a harbor—he said, “Well I’m going to the Groote Schuur Hospital to see my mom. Where do you want out?” I could see the ocean up ahead, so I told him just to let me out at the next corner. I never saw him again. I walked a couple blocks and went down to the water. It was rocky and heavy with kelp. Farther around the corner there was a guy on what I thought was a surfboard, but it really didn’t look like a surfboard. So I walked over, and he was out maybe fifty yards. The waves weren’t even two feet, and it was really kelpy. He took a little bitty wave, and he didn’t even stand up. He fell off and lost the board, started kind of half-swimming, half-crawling over these rocks. The board washed in close to where I was. So I went over and I tried to pick it up, but it was so damn heavy, I could hardly pick it up. I was laughing that the board was so ugly. The guy finally swim-crawls up to the rock where I was. Now, you gotta know that I had hair down to my shoulders—I hadn’t cut it at all for a year or so—and I had a full beard, was wearing an old torn aloha shirt, a pair of shorts, and instead of shoes, I had on these sandals that I had bought in Mexico that were made out of tires. That was really all the Africans wore, too: tire-soled sandals.

Of course, all the English and all those other guys, they’re dressed to the hilt, because these were all colonies at this time. And whether they were German, Dutch, Belgian, or French, they all kinda dressed the same: stark-white shorts and white socks up to their knees, white buck shoes, and usually a pith helmet. They all carried a little swagger stick, and they’d walk down the sidewalk, and if there were some blacks on the sidewalk, they’d whack them with this little short stick if they didn’t get out of their way in time. That was the way it was in those days. Armies, and the white man ruled, and the black man was his servant.

JOHN WHITMORE AND THE DISCOVERY OF CAPE SAINT FRANCIS

JOHN WHITMORE

I’m pretty dark skinned, and I’d been in Tahiti and Australia surfing and all across Africa and out in the sun every day, and I was pretty much as dark as a lot of the mulatto kids were, so when this guy swam up to me and I said, “This is the ugliest surfboard I’ve ever seen,” he responded, “Well, what the hell do you know about surfboards? Who are you?” He couldn’t figure out what I was, but he recognized that I spoke good English, though in a different accent than his. I told him I was from Hawaii and Southern California. “Holy shit,” he said. And then we talked surfboards. “I don’t know everything,” I said, “but I obviously xknow more than you, ’cuz this is an ugly sucker.” And it was. He had made it out of pine and covered it with canvas, if you can imagine. He tacked the canvas on, and then painted the canvas with shellac, so it was all lumpy and hard, and you couldn’t lay on it. It was just ugly. It didn’t even look like a surfboard. It didn’t look like anything I recognized, but he was trying to ride it. He had a Volkswagen Kombi van up on the street, and he said, “You’ve gotta come home with me.” I didn’t have anything else to do, so I said, “Why not? What’s your name?” He said, “John Whitmore.”

Cape Town from above, circa 1959. Photo: Metz.

Oh, wow, the guy in The Endless Summer (released 1966).

Yep. So I get in his car, and we drive to his little house in a place called Bakoven, which is a little suburb of Cape Town. The houses are right on the ocean. It’s not a sandy beach; it’s on a rocky little point. And before we even get there, it’s all dirt roads going down to the house, he’s screaming out the window, “Thelma, Thelma!” (that’s his wife’s name) “Call the mates, we’re having a braai.” I didn’t know what a mate or a braai was, and he was yelling and I was laughing, because the whole thing was a crazy scene. Here I was with hair down to my shoulders and a beard, and I didn’t look like me. I guess that was the only time I ever grew a beard.

The nooks and crannies of Bakoven helped a guy halfway around the world from Laguna Beach feel a little less homesick. Photo: Metz.

Anyway, we get there, and within about five minutes, a bunch of his friends started showing up, and it was just like—it looked like Laguna Beach! There was a white sandy cove and then a rocky point and then another little cove and some more rock…you know, the parallel is the same as Southern California, only it’s in the southern hemisphere. So the temperature’s the same, the ocean’s pretty much the same, and that’s why today, there are literally dozens of South Africans from Cape Town living in Laguna. They have businesses there and they like Laguna because it looks like Cape Town. Not Cape Town the big city with a harbor—that would be more like Long Beach—but you drive a mile around the corner, and then it looks like Laguna.

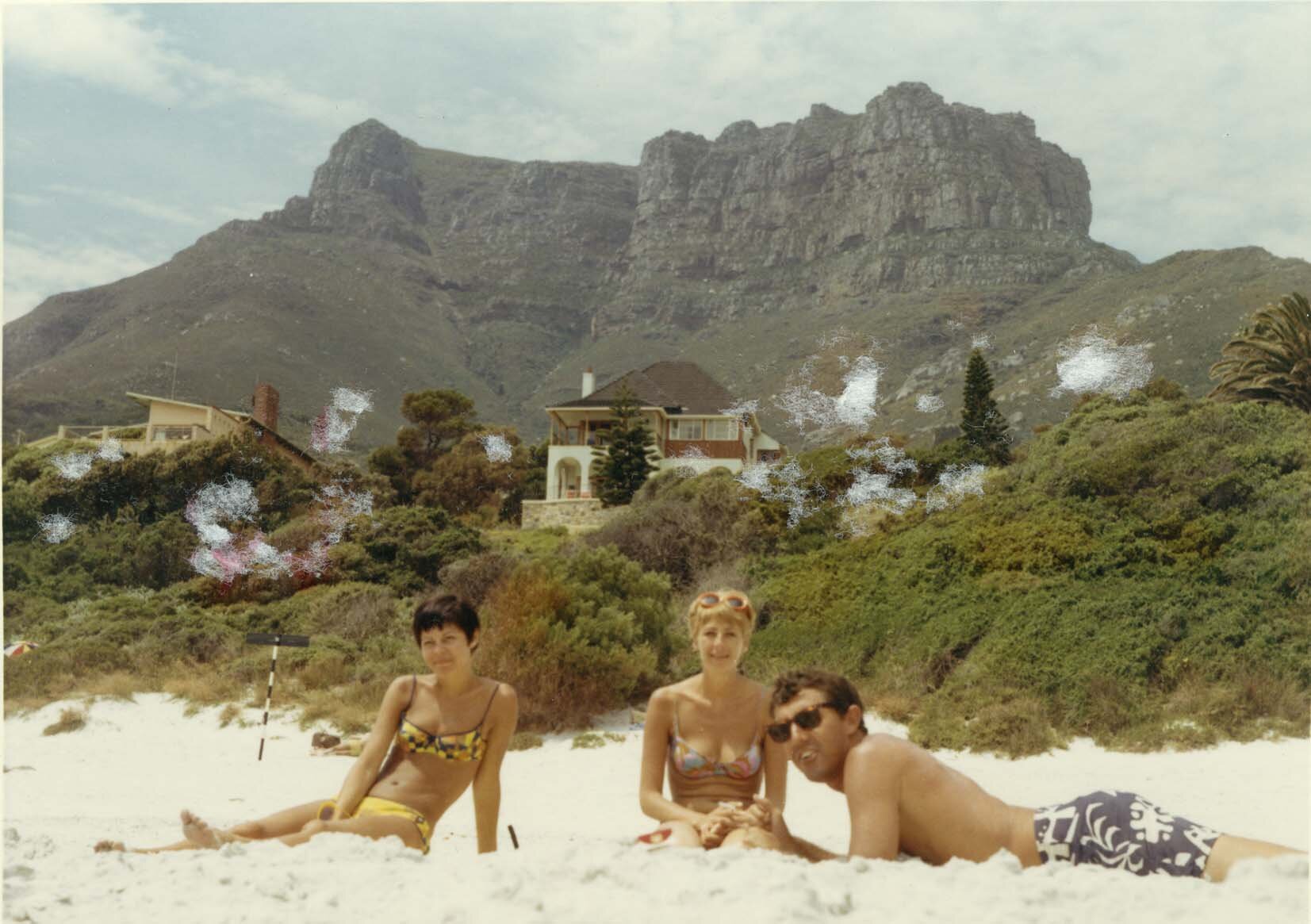

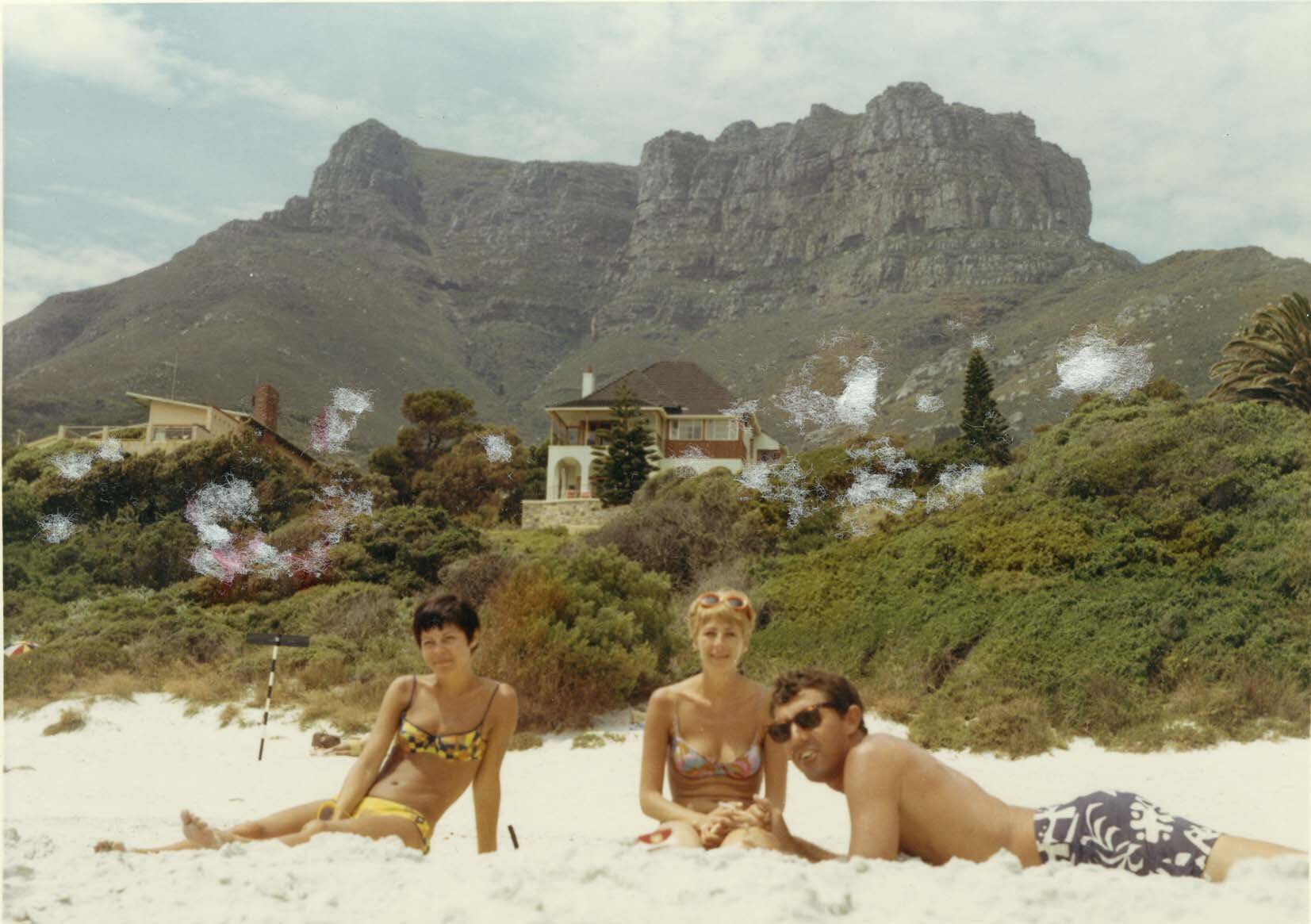

Two girls for every boy! La dolce vita, Cape Town style.

BRAAI

So it was about four or five in the afternoon, they’re bringing out bottles of wine and big hunks of steak, and they eat a lot of sausage there. So John gets a barbecue going, which they call a braai, and they’re throwing big steaks and sausages on and making a salad, and everybody’s drinking wine. I’m thinking, God, is this heaven or what? There’s a bunch of pretty girls in bikini bottoms and little short tops who looked like Southern California girls. They were really friendly and eager to talk, and they were laughing at me because I looked weird and because of my accent. They thought I had a funny accent, so they all wanted to talk to me; and the guys all wanted to know about surfing. Up till that day, I hadn’t been drinking or socializing in a normal way—I mean, occasionally with some white hunters and tourists on safaris, but no gals and not our kind of lifestyle. Boy, that afternoon I got drunk really quickly and we were all laughing and everything, but I ending up falling on the fire. My shirt caught on fire, and they threw me in the back of the Volkswagen. I threw up for about four hours and slept in the van that night. Thelma and John and their two daughters, Shelly and Petta, and a dog named Honey and Patti, Thelma’s little sister all lived there.

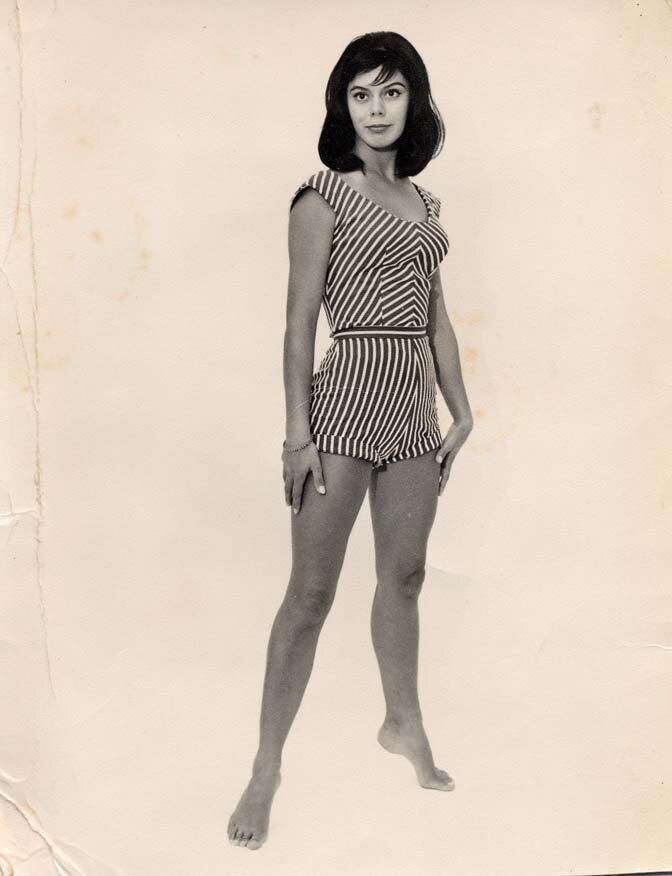

PATTI

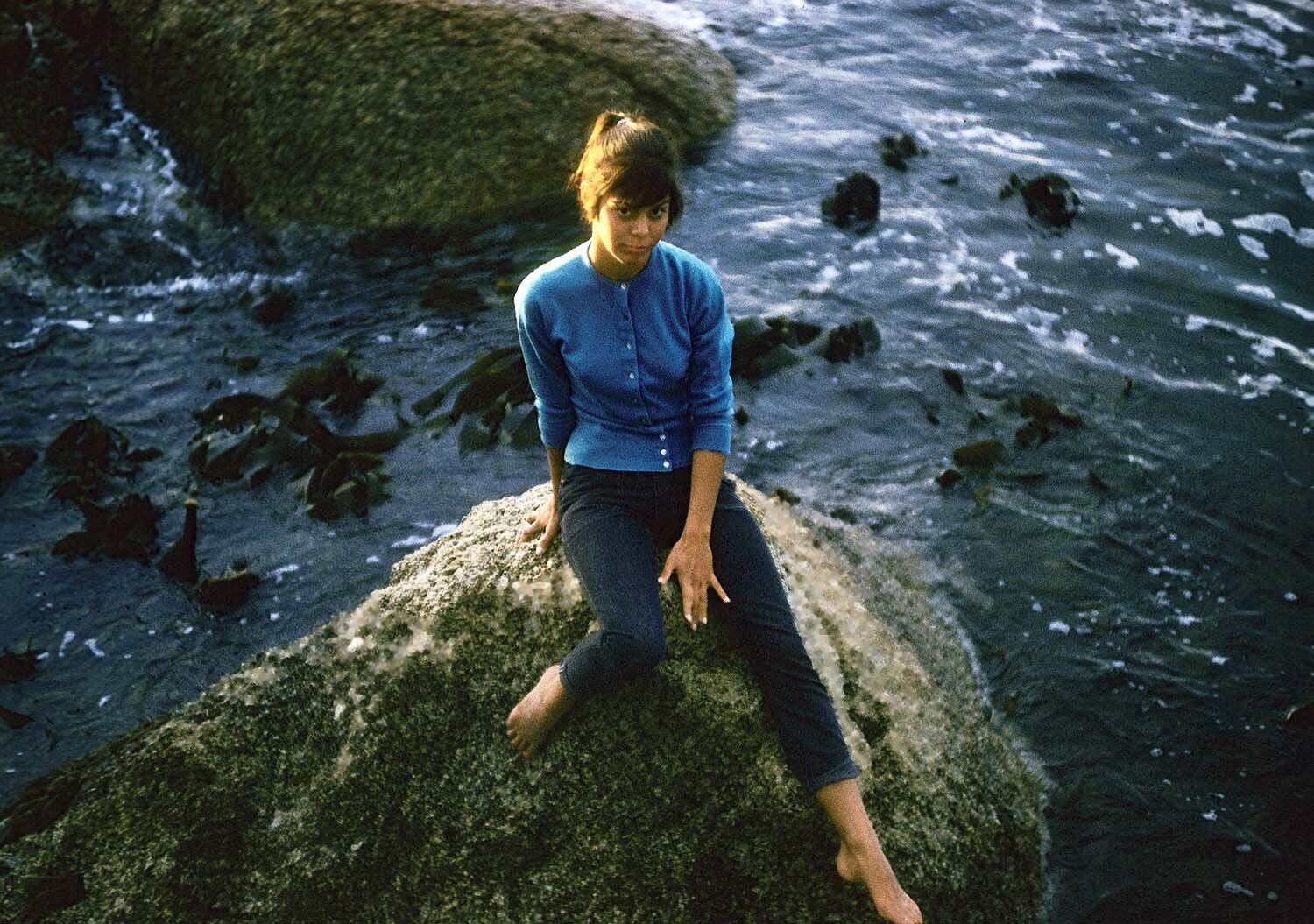

Patti making Table Mountain look good and vice versa. Photo: Dick Metz.

Patti was seventeen, a junior in high school, and I fell in love with her in about five minutes. She was excited—you know, they don’t get any Americans down there, so everybody was enthusiastic about talking to me, learning about where I’d been, and what I was doing. So I fall in love, but I got so shit-faced drunk, I couldn’t do anything good. The next morning, Patti came into the van and woke me up and gave me something to drink. It wasn’t coffee, because I never drank coffee, but something that helped my big hangover and kind of got me going. It was just so neat, because here I’d been gone about a year and a half, had seen all these different cultures and lifestyles and met all kinds of different people, and then all of a sudden, out of the blue—and I didn’t expect it—here I am in a place just like where I grew up, and everybody was acting like where I grew up. We had abalone and lobster, and it was living like we live. I thought, God is this really paradise or what?

I was very excited. Patti was really friendly, and John wouldn’t let me out of his sight because he wanted to know everything I knew about surfboards. He had made two boards based off a photograph. He had a Pan American calendar from 1937 pinned up in his garage. Every month, in those old Pan Am calendars, they would have a picture of somewhere Pan Am flew to. One month it would be Singapore, and the next month it would be the Fijis, and another month it would be Honolulu. So he had a picture of Waikiki and a couple of boards standing against what looked like the Moana Hotel, with a couple of beach boys out there. He had tried to make a surfboard, or two surfboards, from that picture. The photo wasn’t very close-up, and there were the two beach boys obscuring the view, but those boards were standing up, so John got an idea of their shape. But he didn’t know the materials, and his was just a terrible thing. It had a little bitty short fin on it, not deep enough to help you turn it. And you couldn’t even paddle it. There was this big cloth around it and shellac—it was lumpy and hard and it must have weighed eighty pounds. It was just a joke. I used to ride redwood boards, and they were easier to ride than that thing he made.

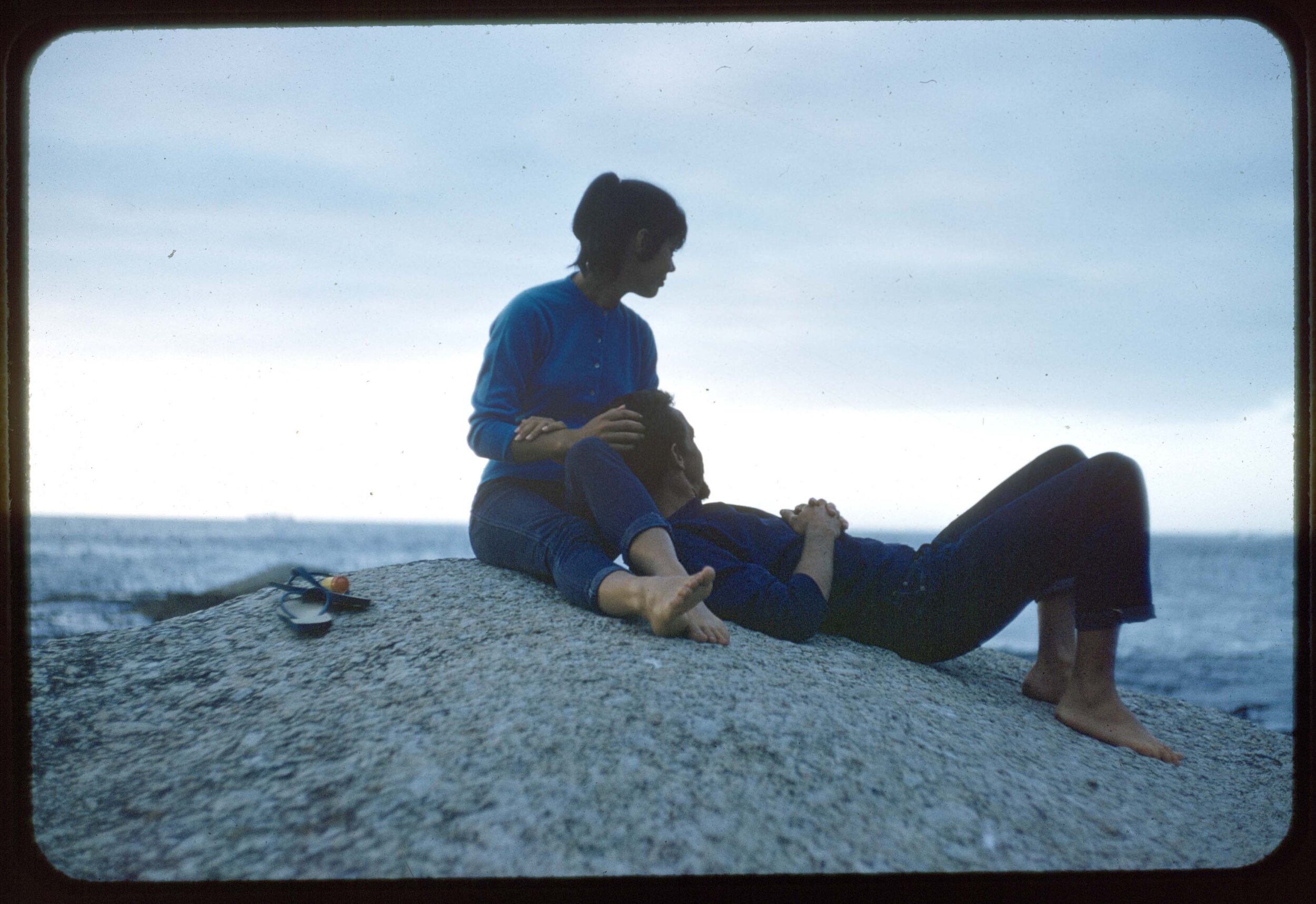

PRETTY PATTI: A SLIDESHOW

The next day he called in to his work—he sold used cars at a Volkswagen dealership—and took a couple days off. We got in the Volkswagen - Thelma, Patti, and I - and drove all around the Cape Peninsula looking at surf. We end up at a place called Kommetjie, and we camped on the beach and went surfing. Just had a great time. By then, I was totally in love with Patti, and she’s pretty much in love with me. It was just really a neat time after all the trials and tribulations that I’d had, sleeping out in the middle of Africa, staying in youth hostels, sleeping in front of police stations.

Metz and Whitmore dodging bull kelp and God knows what else in Cape Town.

JOHN AND THELMA’S PLACE

Back at John and Thelma’s place…they had this little wooden house, a little bungalow, I guess that’s what John called it. So in one bedroom he and Thelma slept. Thelma’s mother, his mother-in-law, slept in the other bedroom with the two baby girls and Patti. So here there were four in the one room, John and Thelma in the other, and they let me sleep on the couch in the living room. And Thelma’s younger brother, Earl Krauss, lived in the garage down below. So they really had a full house. I slept on this couch and ate with them, and I went down to the grocery store and bought $100 worth of food and gave it to them, and they were really appreciative. It was just a simple life. John would go to work every morning; Patti would go to high school; Thelma was working as a volunteer a little ways from the house; and Earl was a painter, so he’d go off painting. I’d just stay around the house because it was right on the beach. I’d walk a few steps down to the beach, and I could surf and dive there for lobster and abalone. I was having a great time, just enjoying it. Patti would come home from school about three o’clock and then we’d play together and hang out. It was just an ideal life.

I’d sit on the beach by myself, and it was so pretty and clear and the ocean was great, and it was just like being in Laguna, only on another continent, in another hemisphere, halfway around the world. I thought, God, I could stay here forever. There were no crowds—of course, there weren’t really big crowds in Laguna when I left in 1958, though it certainly was more crowded than it was in Africa.

I sat out there day after day thinking about alternatives: What am I gonna do? Do I go home, or not go home? Do I live here and marry Patti? All these thoughts were running through my head about life in general and philosophies and stuff I never thought about when I was home. I guess I was busy, working or tending bar and going to parties and going surfing. I was just busy all the time and never thought about those things. I guess I was really starting to grow up and mature a bit. I was thirty-one or thirty-two when I was in Cape Town. I wasn’t a young kid anymore, but god, I just didn’t want to grow up. And I never did grow up, really. I think I’ve always acted like I was nineteen.

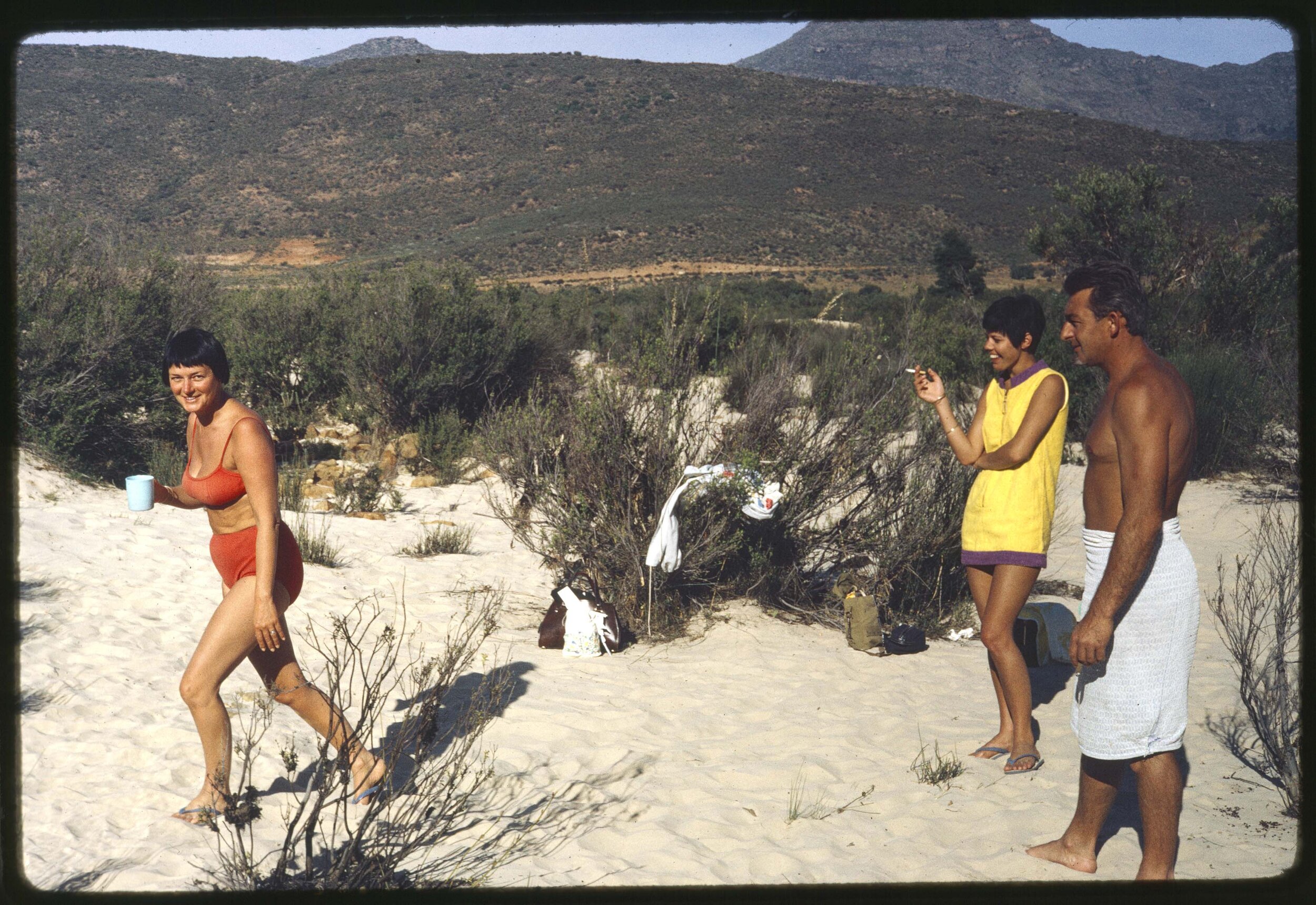

It was just a great time. John would get off on Friday afternoon, and when I was there he’d take extra days so we’d have a three-day weekend, and the four of us would go out. John loved to camp, so we’d go out, up away from the ocean sometimes. There’s desert up there, and Stellenbosch, a town up in the hills, is a great winery town. It’s like the wine country outside San Francisco. And we traveled all around Cape Province [Cape of Good Hope]. It’s like a state; foreign states are provinces in South Africa. There were four then [before 1994]: Natal, Cape Province, Transvaal, and Orange Free State.

Anyway, we really traveled around a lot.

At the house, every night John would come home and we’d cook dinner, usually a barbecue outside, and he’d pick my brain about people and everything about Southern California and Hawaii and where I’d surfed. There were no magazines. There were no movies. He didn’t know anything about the North Shore or Makaha. He’d never heard of them. There was no communication in those days about surfing. You couldn’t go to the library and find a book. There were no books. There was just nothing. So John was absorbing everything I could tell him about every place; and then I was always trying to sleep with Patti, and it was always a battle to get her to sneak out from where she was sleeping with the two little girls and her mom. John was really stoked that I was in love with Patti, because that meant that I was that much closer to him. We became the best of friends. You know how in life, you have one or two or three or four really, really close friends? We had so much common interest, and he was so inquisitive; he wanted to know everything. We just had a bitchin’ time together. We were together morning, noon, and night and talked about everything. He wanted to know about my mom and my dad, all my background, and I wanted to know about his. He was born in South Africa but was of English ancestry.

SURFIN’ SOUTH AFRICA: A SLIDESHOW

One week we’d talk and say, Okay, so this week we’ve gotta go down to Eland’s Bay. It was a couple hundred miles from their place, but we went down for the weekend. There’s neat surf down there, and John said it was a place he’d like to have a home some day. There was a little tavern there and a bar; they call it a shebeen. [correct word?] It was like Newport Beach’s back bay, where the ocean and some other drain water comes in and mixes with the ocean’s saltwater, and there’s all kinds of reeds and stuff in there. But it’s basically a big back bay, part freshwater and part saltwater. There were a few farms around there, one little gas pump, and a lodge that had like 10 rooms and a bar and a restaurant. There used to be an abalone and a lobster plant at Eland’s Bay Point, and they actually processed that stuff, but it had closed. So we’d surf right there on that point. You could drive on the beach. You could drive 500 miles along the beach, and it was all sandy beach. We’d drive up a couple hundred miles and camp on the beach, and surf, and come back. But on that side, the Atlantic side, the water was a lot colder than on the other side, which is the Indian Ocean and seventy-five degrees. On the Atlantic side, it was more like sixty. So it was cold, and we didn’t have wetsuits. We just had these ugly surfboards of John’s that you could hardly surf anyway. It really was more like sightseeing than surfing, because you didn’t go in the water and get wave after wave like you would in Hawaii or Southern California on a good surf day. But it was a great time. I can’t tell you how much fun it was being with John.

He showed me some spots there that he was trying to buy, and sure enough he did buy one, and I’ve been back there many times. Of course he lived down there and actually died down there. He also was into motorcycles, and I was just getting into motorcycles—dirt bikes. He didn’t own one then, but we borrowed a couple and putted around on them. Everything we did was great.

I ended up staying there for three months. One day I told John, “If I don’t leave, I’m never gonna leave.” And he said, “Well, don’t. Stay here and I’ll get you a job.” I told him I couldn’t. That I had made up my mind and I had to go home. But I said that I would be coming back, because I wanted to finish my trip, and I wanted to see some more of Africa. I was supposed to get to the Olympic Games in Rome [by the beginning of August 1960]. And I wanted to run with the bulls in Pamplona. In the meantime, I had been writing to my mom a lot. She was a schoolteacher, and she loved to write and talk and was really inquisitive. So after I’d been there about two or three weeks, I’d written her and told her what a neat family they were, John and Thelma. Unbeknownst to me, she wrote me back in care of Thelma. Thelma is really bright and well-read, and she loves to write. And this was long before there were computers and email and all that shit, so Thelma writes my mom back, about an eight-page letter, real small writing on both sides. So my mom and Thelma become pen pals, and for the four or five months I was there, my mom must have written four or five letters, and Thelma had written her back, and they got to be friends and sent pictures and figured out all their commonalities—they both liked to read—and the books they were reading and on and on.

Anyway, after I told John that I had to leave, he could sense I was getting ready. So one day, it was the middle of the week and he had left for work and Patti had gone to school, I went down to the grocery store and bought big bags of groceries and put them on the table, along with a long note to them that I had already written. I told them that I was leaving and how much I appreciated them and that I would be back. From their place, there was only one road going up the coast to Durban, and I had to take the bus to get there. So I took the bus to where it ended on that road. As usual, John called the house. The phone was right on the deck of his house, and I was usually sitting on the deck or right below the deck on the beach, and I’d answer the phone. So he called the house and I didn’t answer. He just had a sense that I was leaving. So he borrowed a Volkswagen, and he went up to Patti’s school, and he got Patti out an hour early. They knew I had to go; it was no secret. So they drive out to the end of that road, where I’m sitting under a little tree with my rucksack, just waiting for a car to go by and stop for me—cars always stopped, because they were curious.

So I’m sitting there under the tree and I could see this Volkswagen coming, and I knew they’d stop. I didn’t recognize it, because it wasn’t John’s van. So I’m standing up, got my thumb out, kind of waving, and they slow down, which I knew they would, and they get about twenty feet away and I could see that it was John and Patti. They drove up and they were laughing and Patti was crying too, and they were saying, “Oh god, you can’t go. We’re gonna have a big braai this weekend, and we gotta go back to Eland’s Bay, and we gotta do all this stuff.” I finally get in the car and was saying, “This is too hard, I can’t leave.” Now I’m crying too. It was so emotional, because I’d really fallen in love with the family and Patti in particular and the whole countryside. It was like how Laguna must have been in 1910 or 1920. God, it just was so neat. So back we go, back to where they lived. And I stayed another couple months.

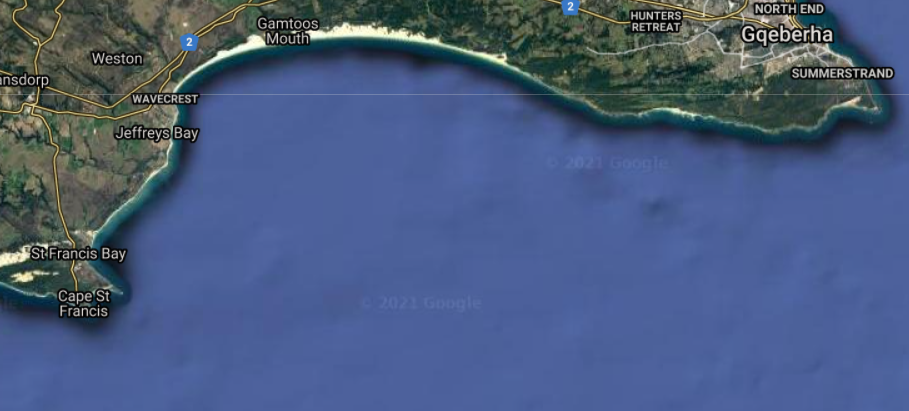

Finally, John said that he’d get me a ride up the coast, that he knew a couple of salesmen who had to go up there, that I should just sit tight and they’ll get me a ride eventually. So I did, and he did get me a ride, and I left a couple months later with this guy. I forget what he was selling, but he was going to East London. John said, “When you go with this guy, he’s not in a hurry, and have him stop. I think there are a couple of places with some neat waves. One of them is called Cape St. Francis. You wanna stop there and check it out.” He said that there were also a lot of other places, that the road goes right along the coast. So away we went.

Muizenberg, South Africa.

To get out onto this road, there’s a big bay, so the peninsula of Cape Town hangs way down, and we drove all around that. On the other side, the east side of the cape, is the Indian Ocean, and that’s where the little town of Muizenberg is. It’s a white sandy beach and kind of a big bay, with neat waves, kind of like Texas. You can walk out half a mile and you’re only chest deep, and there’s just waves all over the place. Not great for surfing, but great for bodysurfing. There are waves everywhere. There weren’t many people there, but we went over there and played in the water a lot because it was so much warmer. Once you started on this road going up the coast, you had to drive around this bay, and then you came back out right on the coast, and that’s where Nizner is—it’s just a spectacular coastline. So we’re driving right along the coast, and I could see the beach. We’d stop and I’d go down, sit on the beach, wearing my M. Nii trunks, jump in the water. It was just so neat, thre was nobody there. It was pristine. It was like you’re discovering Laguna and Dana Point in 1900. I had such an emotional sense about the whole thing. And I still do to this day.

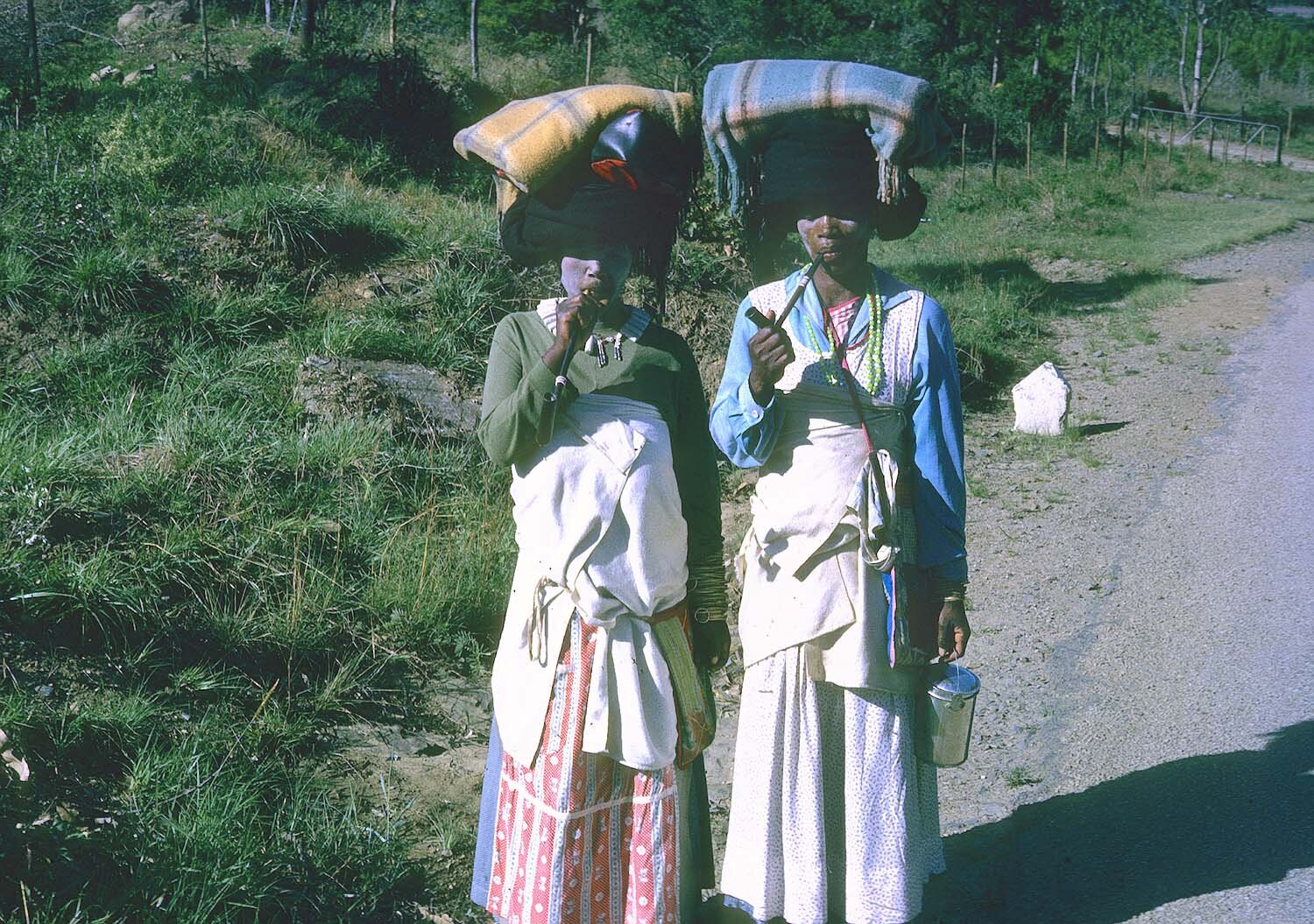

DICK’S BEAUTIES

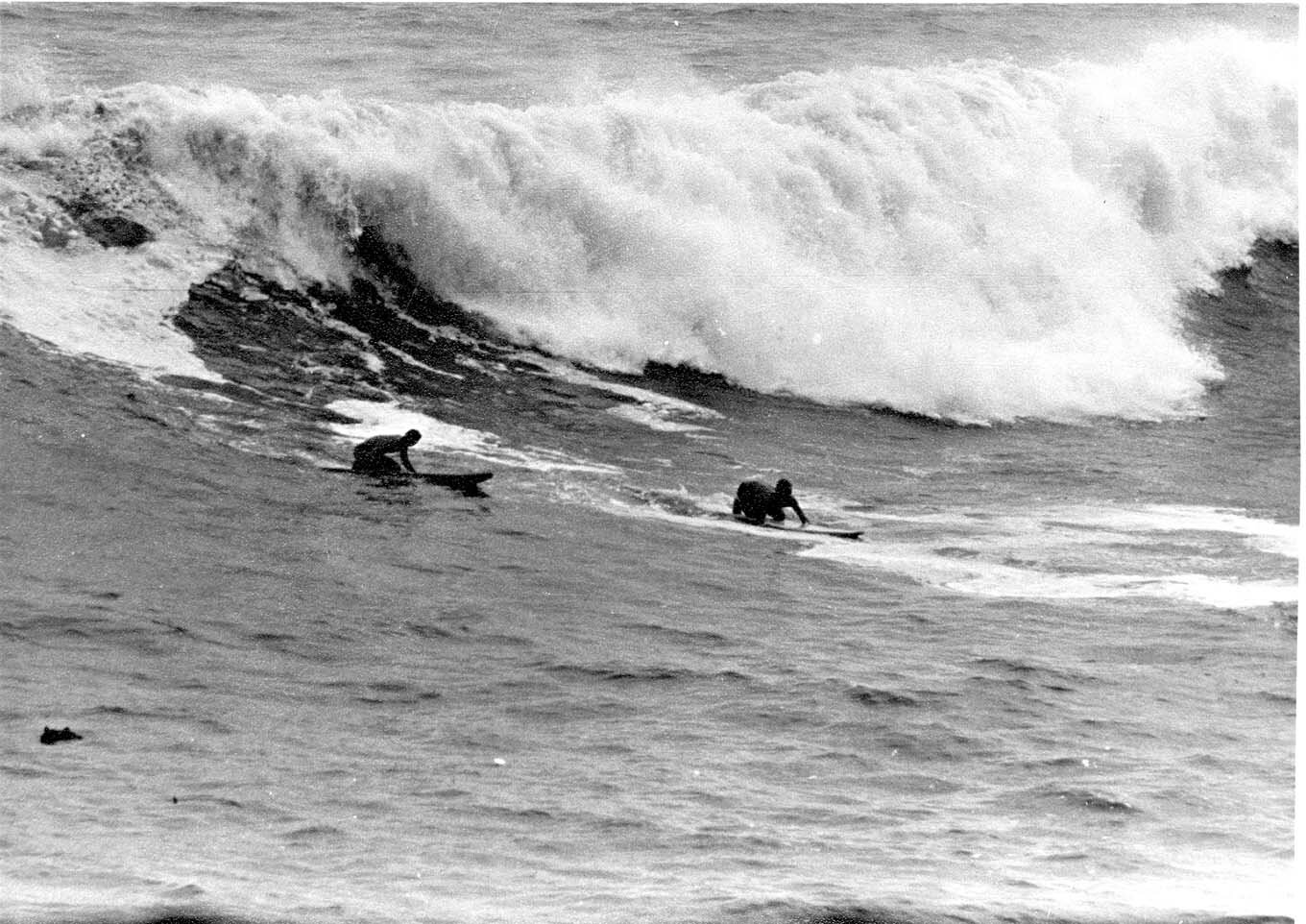

Contrary to Bruce Brown’s effusive, superlative narration in The Endless Summer, Cape Saint Francis isn’t offshore and perfect most days of the year. Indeed, the reality is Cape Saint Francis is as windy as Point Conception and those winds aren’t always favorable. Photo: Dick Metz.

So we worked our way up the coast, and we did get to Cape St. Francis. We drove out there and met the guy who owned a bunch of property and had a general store there. He had a paddleboard that a guy had made for him in Durban. I surfed on that, at JBay [Jeffreys Bay]. (You’ve probably seen pictures of Bruce Brown surfing there.)

Cape St. Francis sticks out the farthest, and it’s pretty windy out there, and there are big waves. Then it wraps into a huge big bay called JBay. There are different breaks, and all along that big bay, inside, there are different points, and every point causes a break. Then it kinda peters out, going maybe another mile or so. Then there’s another point, or rocky reef. There are all these different surf spots, and none of them had names when I was there. But when Bruce got there half a decade later he named one of them Bruce’s Beauties.

I surfed all along there and it was just spectacular, though windy out on the point—and big.

Pretty much the only building around Cape Saint Francis in 1959. It’s different now. Much. Photo: Metz.

I spent five or six days at Cape St. Francis—there was no hotel, no town, not much of anything, but there was a general store. I have a picture of me sitting in front of it, petting the owner’s dog. He gave me a room in the back, and I just stayed there and played on the beach and surfed.

Nope Cape Saint Francis isn’t offshore and firing every day of the year. But neither is the Hollister Ranch or anywhere else. Dick checking it out on a crummy day.

I discovered that Cape St. Francis is the farthest point out, and it’s a big bay and gets really windy. At around noon, it would start blowing, but the inside was protected because it was in the lee. Cape St. Francis had the biggest waves, but it got the windiest the earliest. So we would work our way into what’s now called Jeffreys Bay, and there’s ten different breaks all along there. The farther inside the bay you go, the smaller it gets. There are some great point breaks coming off that point, Cape St. Francis, and wrapping around. It became obvious to me after walking it that it must’ve been five miles, because it curves way in, through all these sandy beaches and little rocky points—that the breaks, at least some of them, kinda ran into one another. You could take off on one and get down toward the end of it, where you’d normally kick out or go in on the white water, but then another point would be beginning its break. They didn’t have names, and there was nobody there surfing, and I didn’t know much about it. Whitmore had told me that all along that coast there were good waves, so I called it Cape St. Francis. I have pictures of it during that trip. And, of course, I told Bruce Brown about it, and he named one of them Bruce’s Beauties. They all have names now. But when I was there, I was the only one surfing those unnamed breaks.

CAPE SAINT FRANCIS - 1959 AND NOW - A SLIDESHOW

For the history of Cape Saint Francis and more photos then and now, click here: https://www.surfline.com/surf-news/real-story-of-cape-st-francis/63424

The general store owner told me that there were a couple guys around who had made some paddleboards, or kind of paddleboards. They were semi-hollow, and I don’t know why both the general manager and John Whitmore had the inclination to wrap those things in canvas after they made them. I guess they thought that would keep them more watertight. Then they would shellac the canvas, so they were these terrible-looking things, and terribly shaped because the canvas would bubble. Plus, it was really rough on your skin. But there was one of these boards there at the time, and there were three or four of them in Durban. I guess this guy in Durban had made maybe four or five of them over a period of time.

How come, since you had worked with shapers in California—your friends like Hobie and Velzy and Kivlin and others —you didn’t think of shaping boards there? Or making boards?

Well, we did. I helped John. But they didn’t have the materials there. There was no balsa wood, and foam hadn’t been created yet—polyurethane foam. Whitmore had tried. What he had done was tried with Styrofoam, though he didn’t have any resin. Resin evaporates Styrofoam, anyway; it just collapses it. So they didn’t have the materials. What John had done was taken blocks of Styrofoam that you couldn’t shape, because it’s a real big cell and very soft. So his was square-railed, like a paddleboard would be. And then he wrapped it in this canvas, and the only liquid he had to cover that was shellac. I kept telling John all about balsa wood and how we were making boards that were so much better. There, the material just wasn’t available. We went to the lumberyard, and they didn’t know what I was talking about. I kept telling John that when I went home, I would send him this stuff so he could make a real surfboard.

Dick second from the right, hanging with the local lovely lads in Durban. Some Anglo and Dutch faces in this mob, no?

After Cape St. Francis, what was next?

After I explored all around there, I eventually worked my way up to East London, and on to Durban. I hitchhiked the rest of the way to Durban. The salesman had gone on his way. I got to Durban fairly early one morning and walked directly down to the main beach. There was a pier there and a little lifeguard tower. So I walked down to the lifeguard tower, where there were seven or eight guys standing around, young guys, obviously beach guys or would-be lifeguards or whatever. I introduced myself and started talking to them, and these guys had the best boards I’d seen in Africa. There actually were paddleboards, like an early Tom Blake. I think it had a drain plug, but they had painted animals or names or something on the noses. I believe there were three boards. So I started talking to them. I must have looked different to them, because I had a beard and a Tahitian hat on, and I’m wearing these sandals made from tires that the Africans wear—but not the white guys; they didn’t wear that stuff. I’m real brown and pretty dark-skinned anyway, though I don’t particularly look like a beach guy, and I didn’t look like any American that they’d seen before, so they’re interested right away. I started talking to them, telling them who I was and where I was from, and I said, “Well, I’d love to go surf one of these boards.” So one of the guys, Harry Bold—

WAX ON, WAX ON THE NOSE

I know Harry! And we’ve kept in contact through the years—what a sweetheart.

Well, he was like twenty years old then. He lives in New Zealand now. I met him on the beach there, it was probably 1959, and he says, “Sure mate, you can borrow my board.” He had some kind of an animal painted on the nose. I asked him for some wax and started waxing up on the nose, where the painting was. I was using a candle, and he said, “What are you doing, putting wax on my painting?” He was all upset. I said, “Well, I wanna walk up on the nose.” They all started laughing and saying I couldn’t walk up on the nose, that I would—they didn’t say “pearl,” but they did have a nickname for it. Anyway, they gave me the board, and they’re all snickering, laughing. They stayed on the beach to watch me, and I went out. I’m not the greatest surfer in the world, but I could do a stretch five, and kind of get up on the nose. So I’m out there on this paddleboard. The waves were small, but they had a curl to them, and I could kind of get in them and get enough momentum to do a stretch five. God, they were all laughing and clapping and cheering. About five minutes later, they all started waxing the nose of their boards and came out to join me.

In fact, they were so enthusiastic and excited that they called the mayor. And the mayor came down and gave me the key to the city. That was a day or so later, because I surfed there several days. Harry and Baron and Jack Wilson and another guy named Eggs were all there cheering when the mayor gave me the key to the city; and then he took me to dinner and gave me a hotel room, which was a big treat. And Baron Stabler, he was one of the guys there, and he made surfboards. (Later on, I helped Baron and Harry start the magazine called Safari Surf.) Baron wrote an article for the Durban Daily Sun. They interviewed me, and I think the title of the article was “A New American in Town Refuses to Join the Rat Race.” Something like that.

How long did you stay in Durban?

I stayed there a couple of weeks, and Harry and Baron and I got to be great friends. Harry told me that he and a couple of others—he called them mates, of course, the whole time—that they were gonna go to England that next summer. I told them to write me through American Express, because I was gonna be at the Olympic Games in Rome [by the end of August 1960]. Sure enough, I get a postcard from Harry when I’m in Europe nearly a year later. So a month later, I hitchhiked over and met Harry in Spain. He was staying with three or four of his buddies on the beach—I forget the name of the beach town now. We hooked up there, and then I invited him to the United States. And I think he did come over in like 1962 or ’63 and stayed with me when I was tending bar, working with Hobie, and had an apartment on Brook Street in Laguna. We stayed close friends. I’ve been back to South Africa several times, and he’s stayed with me two or three times, and now we talk on email and Skype. He’s a great guy, and that’s how that whole thing started: how we met and how I helped them [with boards and surfing]. They always wanted to hear about our magazines, newspapers, movies, and all the stuff we were doing. So when I got home, eventually, I got John Whitmore an invitation to represent Severson [John Severson, founder of Surfer Magazine], selling magazines. Harry and Baron got fired up and started their own magazine, and I got Severson to help them with that.

FATE STRIKES AGAIN

So our chance meeting on the beach that day ended up changing their lives. I could’ve come down an hour later, and those guys might not have been on the beach as lifeguards. And if I hadn’t met them, I might not have stayed. Through those chance meetings—certainly with Whitmore, and later with Harry Bold—their lives, and certainly mine too, were changed. When I met Harry, he was working for Standard Oil at the docks. Standard Oil had a refinery on the big dock in Durban, and his dad worked there and had gotten him a job in the refinery. So these guys quit their jobs and started making surfboards and distributing surfing magazines. They also helped with The Endless Summer and got to be friends with Bruce, and distributed the movie over there. Then they started making clothes.

HANDS ACROSS THE SEA - SOUTH AFRICA TO SOCAL

When Harry and the younger guys from South Africa—like Paul Naude [Billabong] and Shaun Tomson and his cousin Michael —came to America, the first place they sought out was the Hobie shop to look for me, because they knew I was really pro–South Africa. I loved it there. I had a great time, good waves, girlfriends, the whole nine yards. And I kept going back. I’ve been back seven or eight times since that first trip. And once those guys started making clothes…the first was Michael Tomson - he and Shaun Tomson and Paul Naude had all worked for the father of Joel Cooper, who owned a clothing company in South Africa. That’s where they learned the trade.

A classic 90s surf ad campaign by South African Michael Tomson.

Michael came to see me in Laguna, and that’s when Gotcha started. So I was the first to carry all those lines, because I knew those guys, and it gave the Hobie stores something new and unique that nobody else carried. (We were also the first to have Quiksilver.) The business was beneficial to everybody. When these guys came to America, I could help them around and show them where to go, where to stay, what to do, and certainly when I was down there, they did the same for me.

This first trip really was successful in terms of not only introducing us to new and fun guys, but also to whole new cultures—and it really bonded the surfing world. Because up until that point, the surfing world was really Southern California and Hawaii. It was just beginning in Australia, and South Africa was ten years behind Australia. My trip really kind of spread the word, and it was at just the right time—shortly before the movies and the magazines of the 1960s. They were just starting to come out. So once I went around and got all these guys’ names and addresses and started sending them stuff, the whole thing just spread like wildfire. And that’s when, in the mid-’60s, surfing took off like a rocket. Not only in Southern California and Hawaii but all over the world. And the match that lit the flame was kind of me dinging all those locations in the early years, at the beginning of the whole thing. It’s been a great ride, and a great experience for me and for them as well. Anyway, certainly it was important in the history of surf expansion in the modern era.

I can’t believe how many contacts you have, and how much you were involved with surfing’s modern history. It’s pretty amazing.

It really is. It was all kind of a chance-luck thing—right places, right times. And it all started because of where I grew up, and then going on this trip, and then all the chance meetings. I could’ve gone right through and missed Whitmore, never met Harry and those guys in Durban. But I didn’t; it was just luck that I came along when I did. Obviously if I hadn’t, a year or two later, somebody else probably would’ve, but I just happened to be the one in the right place at the right time. And when Bruce made The Endless Summer [released 1966], that showed the world what was happening and brought all the countries together, kind of. You know if I hadn’t made that trip, Bruce probably would have just made movies in Hawaii and Mexico, because in those days, nobody knew anything about Africa. You thought of it as Tarzan jungle and that kind of stuff.

HITCHHIKING UP AFRICA

Where to—and how—from Durban?

After spending a couple weeks in Durban and getting feasted by the mayor and a bunch of other stuff, it was time to get back on the road. I started hitchhiking again, and went right up through the central part of Africa on the same road—there was only one road. Here’s this continent four times bigger than the United States, and there’s only one road. It’s not like here, where there’s a dozen ways to drive from Laguna to New York: you can take the southern route or the northern route or the middle route or whatever. There, and then, there was only the one great north road. So I traveled back up through the Rhodesias—now they have different names. The road split at the town of Broken Hill [which became Kabwe in 1966], in northern Rhodesia. If I went off to the right, it would have been the road I came down from Kenya and what’s now Tanzania. I went left, because I wanted to go into the Belgian Congo [now the Democratic Republic of the Congo] and Rwanda and see all the countryside and the animals and the tribes there.

GOING LEFT

So I got to Broken Hill and split off, and ended up in Jadotville [modern Likasi], which is just over the border in what was then the Belgian Congo. It was late ’59, and it was the first town I got a ride to. It was a colony of Belgians, and there had been a Life Magazine story…. At that time, several African countries were taking back their independence from the colonial powers—the British, French, German, and Belgians. And when I got to Jadotville, there were Belgian troops there, and a bunch of natives, Congolese natives, had raped and killed some nuns in a mission not far from Jadotville. So Belgian paratroopers had been flown in to quell the riots. When I got there, it was all in an uproar. There were fires and explosions. The Belgians, like the Germans and the British, were dressed all in white: shirts, shorts, long white stockings, white buck shoes, and a pith helmet. That was just the dress of the colonies at that time, how the white people, or certainly the political people, dressed. Now there were other guys, like farmers, who didn’t dress like that, certainly. But because I didn’t look like the average white guy—I looked more like a native than I did a haole—I was able to just wander around. I didn’t have any problems.

From Jadotville I got a ride to Elizabethville. They were having a Civil War. The fighting started in Jadotville and moved to Elizabethville. I was staying—I always went to where the white people hung out, because I thought of myself as white—at a little wooden hotel with probably twenty rooms. There was a lot of stuff going on in the street that I was uncertain about, and there wasn’t anyone I could talk to about it. I was told, “Well, we’re having a revolution. The blacks are taking over.” They were shooting the whites, so they were all holed up in this hotel. We went up on the roof, and I have pictures of looking down from the roof into an open square below, and Lumumba, in a suit and tie, was in a Buick convertible. He had a leopard skin—or some animal skin—over his shoulders and his back, and the head of the leopard had been hollowed out to just the skin, and that was on his head. So he was almost completely draped in this leopard skin, in a Buick convertible with a whole bunch of other black guys. There were a lot of troops around and shouting going on.

THE ASSASSINATION OF PATRICE LUMUMBA

[Aficionados of Endless Summer will recognize that name from the narration of the Ghana segment, where Bruce Brown wrily describes a native wiping out: “A west African pullout here called a ‘reverse Patrice Lumumba.’”]

They killed him right in that square about an hour after I was up on the roof. He was shot and decapitated. Then the blacks really went crazy. I have pictures of a school bus that they took charge of. They got on its roof and drove up and down the main street of Elizabethville yelling and screaming. I was under a table in the lobby of this hotel, and they were throwing Molotov cocktails at different buildings. It was scary, and I didn’t know what the hell was going on. Most people didn’t speak English, but I got the gist of what was going on from a few of the Belgians who did.

A parade for Patrice Lamumba. Perhaps the last few moments of Patrice Lamumba.

GETTING OUT OF DODGE

I had no reason to stay there, so the next morning I got a ride up into the Ituri Forest (now the Ituri Rainforest). I rode for a couple of days with a geologist working for the De Beers mining company, another young geologist over there hired to pan rivers and check for minerals that flowed down from the mountains. The public didn’t have cars; every now and then there’d be a big diesel truck. Usually an English truck, big and open on the top. These were bringing commercial crops to the cities, and there were African drivers. (There’s a picture of me on top of one of these trucks—I think it held cotton.) The black driver had a higher position in society because he could drive. He would pick up other guys along the road, maybe people he knew, and they would get a ride up on the top. So there might be ten guys with a bunch of chickens or a pig, sitting on top of whatever commercial stuff was being transported. The driver would also let one or two of them sit in the cab with him.

So I’d be hitchhiking, and sometimes these truck drivers would stop for me. I couldn’t tell what he was saying to the guys in the cab, but he would kick and punch some worse than others, basically saying, Get your ass out of the truck, I want this guy to sit in the cab with me. And they’d do it. There was a social order even among the blacks. They had a structure. The driver, because he had the ability and the job, was considered special. So he would kick these guys out of the cab and invite me in. But I never rode in the cab. I said, “No, no, I get on top.” I have several pictures of me riding up on top with a rooster or a pig or something and all the black guys. They loved it. They’d clap and laugh and look at my shoes and then look at their shoes, and they couldn’t figure it out. They didn’t know what I was. Of course, we couldn’t communicate. They were used to French or a little English, but Swahili was their general language. They had tribal dialects, but Swahili was more widely spoken. So I learned a little Swahili. It was pretty easy: it’s pronounced like it is spelled, pretty much. I used to say “Geno acko nani, ecko sagani:” “My name is Dick, how are you?” Or “Good morning, jambo” is always a good thing to say, because that means good morning. Or good afternoon. “Ecko sagani,” that means, “Come to bed with me.” I had to learn that right away; that was an important phrase.

HOMETOWN GUY

I worked my way through a little town up in northern Belgian Congo called Beni. I got dumped off there one night from a truck, and there was a store, like a general store in America where they sold food. These were usually owned by colonists—a Belgian or an English or German guy—and they would rent rooms if a government person came along. It didn’t happen very often. But they had a building, and they lived there, and they sold something. Colonists who had come to those countries had to find ways to make a living. So I stopped at this place where they let me off. It was kind of rainy that night, and I went into the general store. There was an English car parked outside, which you didn’t often see. There were very few vehicles around. And if you saw any, they were commercial trucks. So I went inside, and there was a white hunter—white hunters always wore certain attire. You could tell who they were. They’d have on a bush hat and a khaki shirt, and they usually had rifles and stuff in their cars. Anyway, there was a white guy in there and he was with an older guy. I started talking to them, and this older guy was obviously a successful businessman. He was probably fifty, fifty-five, and American, I could tell that right away. I asked him where he was from? And he said, “Well you wouldn’t know it. I’m from a little town south of Los Angeles.” And I said, “Well I’m from a little town south of Los Angeles. Where are you talking about?” And he said, “I’m from Laguna Beach.” Then I said, “Holy shit, I was born there! My mom’s a schoolteacher, my dad has a restaurant there.”

So we started chatting, and his name was Smith; I knew the Smith house. It’s a monster house right between—well, now it’s part of Emerald Bay, but it used to be a separate little area, about a five-acre plot right on the bluff overlooking the ocean, right at Laguna city limits. (In those days, Emerald Bay wasn’t part of the city of Laguna.) I knew exactly where it was because right next to there was…we used to call it a scary house. It was a vacant house, like a big haunted Halloween House. As kids we used to hike all around there. Well, it was this guy’s property, and he had a big empty mansion on it. So we had a nice chat; he said he had eaten at my dad’s restaurant many times.

When I asked him what he was doing in Beni, he said he was staying there that night and then going on to Kampala, which is the capital of Uganda, the next day. It was probably 200 or 300 miles away. The white hunter had the car, and Smith had hired this white hunter to drive him on a private tour through the Belgian Congo and into Uganda and maybe Kenya—wherever he wanted to go. I slept outside that night, right in front of the building. There were wooden steps going up into the store and a little wooden-planked deck with an overhang to keep people dry. It rains a lot in the jungle there. That night I slept on a blanket on top of those wooden planks. Of course, the white hunter and the guy from Laguna had the room. Before I went to bed, I was looking at my map and thinking, I’m going on that same road—there was only one; it’s not like there were roads going all over—which headed to Uganda. But I didn’t want to go to Uganda; I wanted to go to the Ituri Forest, which was on the way. So, I’m talking to the store owner, and he tells me, “Well there’s a bunch of pygmies who live up in the Ituri Forest. You oughta take some food up.”

DOUBLE BUBBLE

Do you remember Fleer’s Double Bubble bubble gum? When you’d open up the hunk of bubble gum, there was a little funny paper. Well, I bought a little box of [Fleer Company] Double Bubble and put it in my pack. The next morning it’s drizzling again, and I’m just sitting on the bench out in front of the store, and the white hunter and Mr. Smith get in their car. They had been parked around back, so when I see them come around—I’m just sitting there—I stand up and start waving at them. The white hunter is driving, and Mr. Smith is in the back seat. He rolls down the window and slows down, and I was ready to get in, but Mr. Smith reaches forward and taps the driver, the white hunter, on the shoulder. I couldn’t hear what he said, but basically he was saying, No, no, waving his hand at the white hunter, motioning for him to go forward, go forward. So the white hunter looks at me perplexed, and I’m thinking, What the fuck, you know who I am. It’s not like I’m some hippie out in the woods—though I certainly looked like a hippie out in the woods, but I wasn’t and he knew that. They drove on; they wouldn’t give me a ride. I was in total shock. They were driving slow, and I picked up a rock and threw it at the car. It didn’t break through the window; it just shattered it, made a cobweb. They just kept on going! I couldn’t believe it. Africans had kicked other guys out of a car to get me on, and here’s a guy from my hometown who wouldn’t give me a ride. I was appalled. I was so pissed off, because rides were hard to come by.

Somewhere along the way during that trip, I waited seventeen days for a car. It wasn’t unusual at all to wait two or three days. That was pretty commonplace. So here’s someone I’d met the night before and talked to—and from my hometown!—and he wouldn’t give me a ride. God, it was just beyond my comprehension.

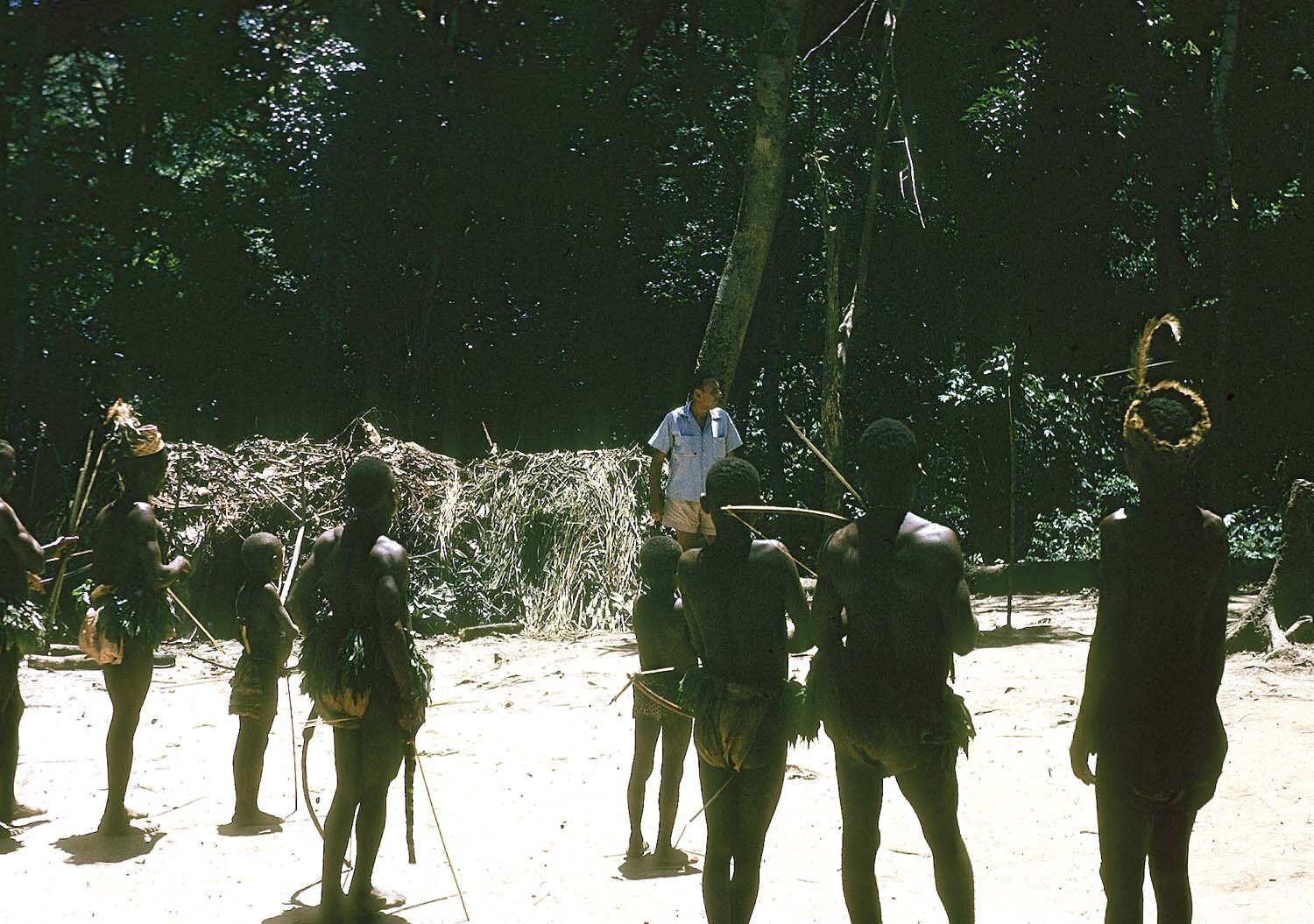

PYGMIES DIG ME

So what did you do? How did you continue on?