On Sunday, July 23, 2007 Vic Calandra and Joey Everett were competing in the 10-mile Tommy Zahn Memorial paddleboard race off the Malibu coast. A Los Angeles County Lifeguard at the time,Everett was paddling prone on an 18-foot Unlimited Class paddleboard while Calandra was standing up on an 18-foot board, using both arms to move a single paddle through the water.

As you read this story, keep in mind this is a 14 foot white shark, about the size of the shark that harassed Vic Calandra and Joey Everett helped beat up. This is a shark that came ashore in Baja because it had been injured by a boat. But to see a shark this big a mile out to sea and charge it. Well that’s something.

They both were contenders in their divisions, about two-thirds of the way to the finish line and around a mile offshore, when they both were plunged into a battle for their lives with an aggressive 12-foot shark. Facing down an Escalade with teeth, their instinctive urge of “fight or flight” gave them two options: run, or defend themselves. Too far offshore to outrun the shark they decided to fight, using both hands and that single paddle to beat back the repeated aggressive moves of the shark, saving their own lives and possibly the lives of other paddlers who came in their wake, unaware of the danger.

Joe Quigg on the left and Tommy Zahn on the right with Diamond Head behind them. Photo taken in the 1950s in Hawaii, with both surfers touching a “Malibu chip” balsa surfboard. Photo: Matt Kivlin. I think.

The Tommy Zahn Paddleboard race is dedicated to one of the all-time great Los Angeles County watermen. Born in 1924, Zahn was in his prime as a surfer, paddler and lifeguard from the 40s into the 50s, when the California surf and ocean scene was bubbling, and watermen could make a living as lifeguards, stuntmen and actors.

Zahn was movie-star handsome and at one time dated Marilyn Monroe, taking her surfing off Surfrider Beach in the late 1940s: “She was in prime condition,” Zahn was quoted in Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe by Anthony Summers:. “Tremendously fit. I used to take her surfing up at Malibu-tandem surfing, you know, two riders on the same surfboard. I’d take her later, in the dead of winter when it was cold, and it didn’t faze her in the least; she’d lay in the cold water, waiting for the waves. She was very good in the water, very robust, so healthy, a really fine attitude towards life. I was twenty-two when I met her, and I guess she was twenty. Gosh, I really liked her.”

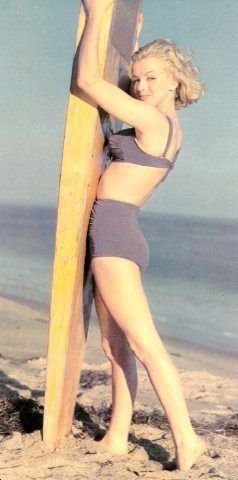

Marilyn Monroe posing with a surfboard for a modeling shoot, but she wasn’t just a poser.

Before she was the biggest movie star in the world, Marilyn was a cute surfer girl tandem surfing Malibu with Tommy Zahn

Zahn was also tremendously fit and in prime condition and he is considered a legend among LA County lifeguards, surfers and watermen. Craig Lockwood wrote about Zahn on the www.eatonsurf.com website: “Born in Santa Monica in 1924, he grew up on the beach and served as a lifeguard for all his adult life, working for the cities of Santa Monica, and Newport Beach, as well as Los Angeles County, and the State of California. As Lieutenant Tom Zahn, skipper of the L.A. County Baywatch, he was awarded the Medal of Valor. As a surfer he had ridden big North Shore Hawaiian surf with the sport’s pioneers in the late 1940s, and early ’50s. As a paddleboard racing champion he established a number of long-standing records, including his 9 hour, 20 minute solo Molokai/Waikiki Channel crossing in October, 1953, and his 1958 Catalina Channel crossing record which stood for over 20 years… Zahn, however, never considered his ideals or achievements as credentials; aggrandizement was not his style. Instead, Zahn esteemed order and lived a life of economic simplicity. While he received numerous awards over the years, and was often cast as a ‘hero,’ he felt no need to be dramatized as one. He ignored celebrity. Tom Zahn wasn’t a grandstander, he simply stood in the light of his deeds. He didn’t bask.”

Nachum Shifren in the middle with Tom Zahn to the right and ??? to his left. On the beach at ???? Photo: ???

Zahn died 1991 at age 67. In 1994, the Tommy Zahn Paddleboard Race was started in his honor by Rabbi Nachum Shifren – the surfing Rabbi – and in 1997 it became a part of the Malibu Boardrider’s Club Call to the Wall surfing competition.

In 2007, the Tommy Zahn paddleboard race had 45 paddlers in six classes – Mens’ and Women’s Unlimited, Mens and Women’s Stock and Men’s and Women’s Stand Up. The Stand Up division was a relatively new innovation, which had around 20 competitors standing up on boards ranging from 12 to 18 feet, using both hands on a single paddle for forward motion, like Venice gondoliers.

The Tommy Zahn Paddleboard Race let Zuma Beach, went around Point Dume and headed straight for the Malibu Pier, which placed the paddlers about a mile off Cher’s house at Puerco Canyon.

The race left the Zuma Beach lifeguard tower at 9:00 AM on Sunday, the 23 of July for a 10-mile downwind race that is considered middle distance by experienced paddlers. Conditions were slight overcast with no wind and very little swell, which the paddlers loved but the surfers competing at the Call to the Wall didn’t.

At the time, Vic Calandra was a AGE??? year old PROFESSION???, who lived in the El Nido area off Corral Canyon (in a house that nearly burned to cinders a few months after the shark incident in the Corral Fire of November 24 - 27, 2007). Vic was one of a regular platoon of stand up paddle surfers who could be seen all around Malibu, from First Point to Little Dume and off in the kelp beds, getting a different kind of workout from the balls of their feet to the backs of their necks: “I was vying for third with a stand up paddler,” Calandra said, three days after his Close Encounter of the Jaws kind. “There were two guys in front of me and I was about even with another guy who was about 300 yards farther out than I was. We were clicking along at a good pace and had passed Paradise Cove and got past Corral Beach and we were almost to the incline where Malibu Road starts. I was about a mile and a quarter offshore and the other guy was about 300 yards farther outside then me. Usually on long distance races I will take my IPod with me which cuts me off from the ocean noises, but this time I chose not to listen to my IPod. I could hear what was going on around me. The ocean was completely glassy when I heard something cut the water. That is not unusual because you see and hear all kinds of things when you are paddling. Usually it’s a seal or sea lion or a dolphin or sometimes a fish breaking the surface, but shark is always in the corner of your mind. But this had a different noise so I stopped paddling and turned around and saw something big in the water behind me. It had a different kind of surface track and I thought it might be a dolphin, but the fin kept coming out of the water until it was 18 to 24 inches high. A big fin, and I knew what it was.”

As seen from the sea, Cher’s stately pleasure dome at Puerco Canyon and Pacific Coast Highway. The attack happened about a mile offshore from here. For the inner view of this place, check out: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/gallery/step-inside-chers-malibu-home

Big sharks are not common along the Malibu coast, but they are not unheard of. During the spring and summer, pregnant white sharks will come close to shore to give birth to their young along the coast – preferring sandy beaches like Will Rogers State Beach. The mothers leave immediately after giving birth, because they will eat their own children if they stay around. Newborn white sharks must immediately fend for themselves and grunion are an easy source of food, so the Santa Monica Bay is a sort of maternity ward for white sharks.

Over the years there have been a number of close encounters and possible attacks. In 1989, two UCLA students disappeared while kayaking between Latigo Point and Point Dume. The woman was later found dead in the water off Channel Islands Harbor in Ventura County. She had a large bite on her thigh which was identified as a white shark wound. The man was never found, but when safety officials examined their kayaks, they found a gash in the bottom of one, which an engineer estimated was made by an animal that weighed over a ton, moving at more than 15 MPH.

Most who go into the water around Malibu are unaware of the possibility of a close encounter, but lifeguards know the possibility exists. Sightings of fins are common, but 99.99 per cent of the time the fin is a dolphin dorsal or the head of a seal or sea lion. This time, it wasn’t.

Calandra was essentially alone, more than a mile offshore, and he had no doubt that he was being tracked/stalked by a very large shark: “I veered quickly to the right because I have a steering mechanism on the board, but the fin tracked with me and that is when I knew it was following me. I caught glimpses of the shark as it got closer and it was big.”

Calandra continued paddling, standing up and looking over his shoulder as the shark closed the distance on him, from 100 feet behind to 50 feet to 25 feet, the fin getting bigger as it got closer and Calandra getting an all too good overview of just how big this fish was: “It looked like a small submarine, the way the water was running off the back of it, on both sides of the fin.”

The shark caught up with Calandra and nudged his 18-foot paddleboard from behind. “I slapped at the water with my paddle just as the shark turned on its side as it came past me,” Calandra said. “I got a full look at its belly and the full mouth and its head and eyes. The shark was about two feet under the water but I was about six feet above the surface and I saw all of it. I would say it was 12 feet long, but it was the girth of the shark that really impressed me. There was three and a half feet of shark on either side of the fun. Those things are just huge.”

In a situation like that, humans confronted by sharks have two choices: Freeze, or keep moving. Sharks are attracted by sound and vibration more than by sight, and Calandra might have done better to just freeze, but he felt the shark had a bead on him and it’s hard to stay still when a Fed Ex truck with teeth is stalking you, so he continued paddling: “The shark came back around in another pattern from behind me so I dropped to my knees and started striking it with my oar, hitting the head and the fins and trying to get the paddle deep into the water to make contact. I knew I was in peril as this thing was definitely aggressive and not going to be scared off easily. The shark came under my board laterally three or four times as I continued slapping at it, standing up again to stay as far away from it as I could. There was nothing else around me and I knew I wasn’t going to make it a mile and a quarter to shore with this thing on me, and I knew my only chance was to get to a boat or get some help from other paddlers.”

Calandra’s lonely dance with the shark continued for several minutes and that allowed other paddlers to catch up with him: “I saw two paddlers coming up and thought that was my only chance,” Calandra said. “To get someone with me to scare this thing off.”

There were actually three paddlers within earshot of Calandra, and he managed to attract the attention of one, whose behavior followed in the spirit of Tommy Zahn, because what Joey Everett did next was extraordinarily brave.

In 2007 Joey Everett was a 37-year old LA County Lifeguard stationed at Zuma Beach. With experience as an LA City Fireman and a lifeguard, Everett had “been in some hairy situations” before. He was paddling an 18-foot Unlimited Class paddleboard and was about six back in the pack when he was diverted by a call for help, and his race was transformed into a different kind of battle: “We came around Point Dume and passed Paradise Cove and I think I was about ??? yards off of the start of Malibu Road. Vic was probably ??? yards outside of me and I could hear him yelling for help. I didn’t know what was wrong at first but when I was about 100 yards away I did a push up and saw a fin. I kept paddling and when I was about 50 yards away I saw the shark swimming aggressively and when I was about 25 yards away I saw the shark bumping the tail of Vic’s board. That is when I knew an attack was imminent.”

Others who have been involved with shark attacks always talk about the “fight or flight” instinct immediately taking over once they realize an aggressive shark is in the water with them. Everett was on an 18-foot paddleboard, and, powered by adrenaline, he could have been on shore in no time, but as a lifeguard he is trained to help those in peril, and Everett had no doubt the stand up paddler was in deep kimchi: “We have a little training in situations like this and at the lifeguard academy, what it says in the manual is to hit a shark on the head and the nose. So I went by the book, figuring if we could get the shark off Vic’s tail we might have a chance. Truthfully, I thought we were both going to die at that point and the fight or flight instinct took over. We were too far from shore for flight, so we had to fight.”

As Everett came paddling to the rescue, Calandra was still dealing with this shark that refused to go away: “I got the attention of one and he turned his board toward me and started heading my way. The shark fin was following me still and I dropped to my knees again to strike at it. I got to my feet and headed toward the paddler, yelling at him and talking to him as he approached. He yelled, “Don’t fall! He’s on your tail. I’m going to try and ram him!’”

Vic and Everett got their boards paralleled to each other and had a brief conversation: “I asked him how big the shark was,” Everett said. “because he could see it from above and I was at sea-level. He said it was at least 10 feet and was a white.”

Everett had seen thresher sharks during his time as a lifeguard, but never one of the bigger, more aggressive mammal eaters. He knew the shark was either a mako or a white shark, both of which are aggressive and dangerous and not reluctant to attack humans: “I know that makos are known to attack boats,” Everett said. “which lead me to believe it was a mako. But Vic had a better angle on it from me as he was standing up and looking down on it, and he was certain it was a white.”

Whatever it was, it was trouble with a capital T. Everett knew it was about to attack Calandra and possibly turn on him, so Everett went by the book and hoped for the best. “It was like a barfight,” Everett said. “I paddled up and over the shark with my board and started swinging. I was screaming at the shark and bumping it with my board and hitting it on the nose but I had no idea if that was scaring the shark or making it more aggressive. I saw the dorsal fin of the shark and the nose but didn’t see the whole thing, but the nose of the shark was as big as my torso.”

Calandra did the best he could to fight off the shark without falling in the water: “I couldn’t see this as well as Joe, but he said the shark’s mouth was open and extended up and out of the water. He struck my board with its snout and my tail skidded out and that is when Joe said, ‘Don’t fall! He is on you!’ We crossed paths and then we were parallel to each other and the thing started coming at both of us. The fin was in front of us and we were striking it as much as we could and watching out for each other. We moved collectively. He was moving one way and trying to get a visual and that went on for about three or four minutes.”

Everett’s senses were very clear because of the adrenaline, and he believes it was Calandra’s paddle striking the water, and not striking the shark, that scared the shark off: “At some point the shark submerged and disappeared, but we didn’t know if it was gone or if it was going to come flying out of the water like you see on the Discovery Channel,” Everett said.

The Aquarius charter fishing boat.

Calandra continued: “Then we saw the Aquarius [a commercial fishing boat that launches from the Malibu Pier] about 400 yards away. Joe said, ‘We have to get there and call Baywatch,’ but I saw there was no way we would make it. I saw a smaller fishing boat about 150 to 200 yards away so we aimed for that, kind of stair-stepping along. He would paddle 20 yards and I would watch his back, then I would get ahead of him and he would watch mine. We got to the boat and Joey pulled his board in and got on the radio and called Baywatch. I have no idea why I stayed in the water. I was kind of in a daze by that time and I knew there were other paddlers who had gone past me. I was closer to shore and felt safer, I guess, so Joey stayed in the boat to wait for Baywatch and I took off to catch the other paddlers and warn them. I figured Baywatch would come up to me along the way but they didn’t so I finished the race.”

Hey man, thanks! Photo: Ben Marcus

As Calandra continued paddling, Everett stayed behind to direct the La County lifeguards who came to the rescue in the Baywatch boat and also a WaveRunner: “I was no longer a contestant,” Everett said. “I had to alert Baywatch who were unaware of what was going on. I got on Channel 60 which is the emergency marine channel and alerted the Baywatch boat, which had been tailing along with the race making sure everyone was okay. They got a WaveRunner with a rescue sled and two guards in the water and they did all they could to make sure everyone was okay.”

Calandra didn’t win that match race for third place, but he did live to tell about the experience. Along the way, Calandra saw some girls in kayaks meandering along in the kelp beds, and he told them to get to the beach right away. Calandra got to the beach shaken and stirred, with no doubt he was alive because a lifeguard who knew what he was doing came to the rescue: “The only reason this thing didn’t strike me was because Joey was there to fight it off. I had seen this guy around but didn’t really know him and there is n doubt he saved my life.”

Kelly Meyer was one of the women in the standup division who came along in the wake of the shark incident: “I was one of two women in the stand up race. I was behind where Vic and Joe had been attacked and where Simone was by about twenty minutes. I was paddling right toward where the attack had taken place. I saw the helicopter, the rescue jet skis and the lifeguard boat but I had no idea what was happening because NO ONE told me anything. So I just continued and finished. I enjoyed the race and I would go back out there today but I am wondering why no one felt it was in my best interest to alert me of the possible danger?”

There were a number of female contestants in the race, and Everett got back on his board and rode shotgun with some of the women, making sure they finished the race safely: “One of them thanked me by buying me dinner that night, so that was okay,” Everett said. “And Vic has called me a few times, too. We both know we were in deep shit for a while there, but we worked together and got rid of that big fish and it turned out okay. I have been a fireman and a lifeguard for many years, but this was the scariest thing I have seen in my life.”

The battle between prehistoric animal and modern men was the talk of the Malibu coast in the days following the battle. Some local residents pointed fingers at the Aquarius, the commercial fishing boat which essentially chums as it moves along, with bait being thrown overboard by fishermen along with the refuse of cleaned fish.

Others noted that the Monterey Bay Aquarium shark pen which appears off the coast at Paradise Cove every summer might have something to do with it: “Maybe one escaped from there and was pissed,” said paddleboard competitor Bill Kalmenson.

On July 29, 2009, Dave Ogle was filming a helicopter promo video when he spotted this white shark cruising about a half mile offshore from Malibu Road. This shark seems to appear every July, causing some citizens to dub it Miss July. Video from Dave Ogle. Full story: https://www.surfer.com/features/great_white_shark_in_malibu/

The truth is, there are sharks along the Malibu coast, and Everett and Calandra were neither the first nor the last to encounter them, but they will certainly go down in local legend as the two men who fought off a big shark and won.

(Los Angeles County awards the Medal of Valor to peace officers and rescue personnel who act above and beyond. In ???? I sent this story with photos to the right peopole at Los Angeles County, stating: “Your guy charged a 14-foot white shark a mile out to sea and punched it out. If that’s not valorous, I don’t know what is.”

Los Angeles County agreed and on August Everett was officialy awarded the honor at a dinner.

Read about it here: https://www.dailybulletin.com/2008/08/01/pair-lauded-for-rescue-of-swimmer/amp/ )

Vic and Joe talking story a few days after the thwarted attack. Still a little incredulous about what happened, and how they got through it. Photo: Ben Marcus

THE LEGEND OF MISS JULY

SHARK SIGHTING IN MALIBU: JULY 24, 2009:

https://www.supatx.com/malibu/shark/

Great White Shark Sighting Stirs Malibu: July 22, 2010

https://www.surfer.com/features/great_white_shark_in_malibu/

The Return of Miss July: June 29, 2011

https://patch.com/california/malibu/bp--the-return-of-miss-july

White Sharks of Malibu Part One: August 18, 2012

https://patch.com/california/malibu/bp--white-sharks-of-malibu-part-one

Great White Shark Activity Reported Near Malibu Beach: July 14, 2021

https://patch.com/california/malibu/great-white-shark-activity-reported-near-malibu-beach