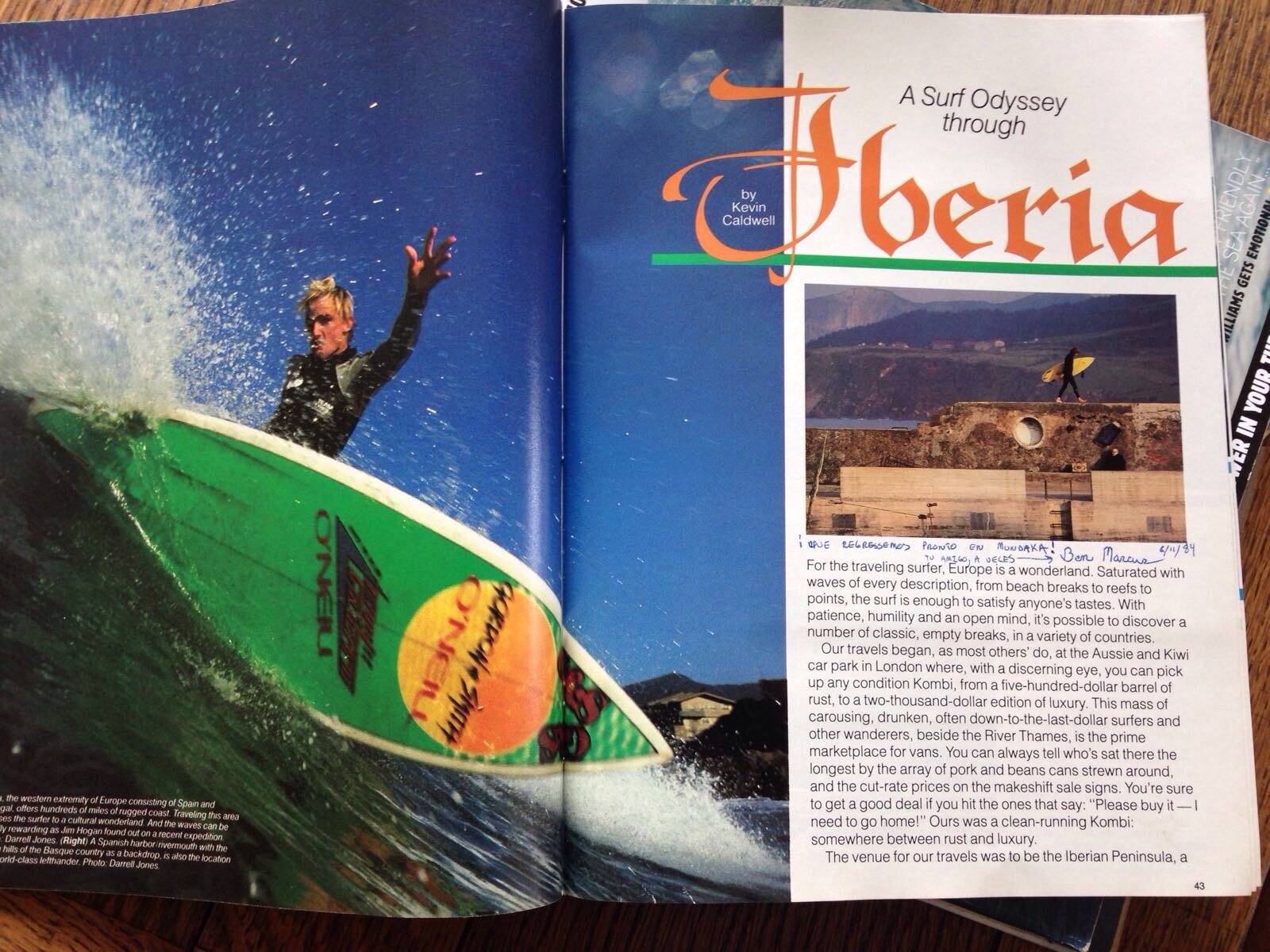

A detail from Pablo Picasso’s famous Guernica also visually captures what it feels like to get caught inside at Mundaka on a big day. Or to travel with Australians. Photo from Internet.

“You wouldn’t read about it!” Aussies use this exclamation to express frustration or exasperation when Fate, The Odds or some other supernatural force has turned against them. You will hear it muttered or shouted at horse races, in sudden rainstorms, and after elections. You will also hear it said around the ocean.

I’m from California but have been known to associate with Australians. I first heard that expression leaving Biarritz to travel south with the Australian Odd Couple - Maroubran Chris Ross aka Oscar and Mauritian Ronald Jean Marc Dupont Louis (RJMDL) aka Felix.

We met in the youth hostel in Anglet on the Cotes des Basques, Biarritz circa 1984. We surfed, we cajoled. They teased me about American “gridiron” football. I teased them about their convict ancestry.

Miki Dora was living behind that hostel at Chambre D’Amour in a green Mercedes bus. He’d just gotten out of prison and was more than a little glad to be a free man in Paris - or anywhere. We surfed with him and I might have unknowingly aided and abetted him in stealing $2000 in traveler’s checks from a Canadian girl staying in the hostel.

(I wrote a story about that Da Cat encounter/incident and sent it to David Rensin for the Dora book he was working on. It didn’t make the cut. It should have. Oh well.)

We surfed, we hung out with Dora, we ate, drank and were merry on the Basque Coast of Spain in the fall of 1983. Of all the exotic meals I’ve had around the world - from French Onion Soup at the Seaview in Tonga to the famous churrascaria Porcao in Rio de Janeiro to oub lunches in County Sligo, Ireland - one of the most memorable was dippin big wads of fresh baguette into huge mugs of coffee in the youth hostel at Chambre d’Amour - as Oscar and Felix serenadedme with bawdy renditions of Chanson de l’Amour:

Chanson d'amour, ra da da da da, je t'adore

Each time I hear, ra da da da da, chanson, chanson, d'amour

Simple mais superbe. We got surf, we got drunk, we ate mass quantities of croque monsieur. We dipped deep in la dolce vita in Biarritz and then Fate threw me in the car with these scoundrels to head over the Pyrenees and into Spain.

God’s=eye view of Napoleon’s private summer residence.

Leaving Biarritz, we rounded a corner near Napoleon’s summer place, when the boards flew off the roof of the Renault, almost nailed a guy on a motorcycle, then crashed onto the pavement.

“Shit, the boards!” said Oscar.

“You wouldn’t read about it!” said Felix. “Stop the car!”

Two days later I heard the expression again. We stopped in lovely San Sebastian where we scored some decent waves and paella and were headed south. We were halfway through a highway tunnel when the car started bumping.

“Aw, you wouldn't read about it,” said the Odd Couple in unison. We fixed the flat, continued south, and pulled into the fishing village in the evening.

I lived in the fishing village, and surfed the Point for two months. Life there was full of surprises, and I had the occasion to use that expression a number of times myself.

To give you an idea how perfect the Point was, I got the best tube of my life there. It was a fluke - a happy accident.

English Duncan, Ronald Jean Marc Dupont Louis and Chris Ross. Waiting for the tide to drop or the bars to open or something. If the photo is a little blurry - well, we all were. Photo: Ben

There was no surf the first three days of our visitation at the fishing village. The swell came up the morning after a huge fiesta: Todos Santos (11/1, my lucky number!). The fiesta took place at the town Picasso made famous. It was a full-throttle rage, and I was up drinking and fiestaing all night. I had to wait until sunrise to take the train back to the fishing village after Oscar head-butted a local guy, and the Odd Couple drove home without me.

“You wouldn’t read about it! Bastards bail out without me!” I mumbled, as I rode the train home.

(Turns out Ron and Chris bailed on me to escape with their lives. As Chris remembered it, decades later: “Firstly RJMDL and I were in a bar, out the back. When this Spanish Criminal came up to Ron and started hassling him, he started putting hands in Ron’s pockets trying to take money out. I said to Ron he should leave. I had Ron’s jacket and my leather jacket in my hands. Ron escaped the Spanish Basque Terrorist. So then he turned his attention on to me trying to grab my leather jacket. I told him in my best Spanish learnt from all the old westerns I watched as a kid, to basically fuck off. Well he started to whistle and call out to his so called ISIS friends to help him. At this stage I asked the couple next to me. “Do you speak any English?” A girl replied “Si” and I asked her what he wanted and she said, “He is saying you stole his leather jacket.” I replied well this jacket is made in Australia and I don’t think he would own one from there.

For those unfamiliar with the concept of the headbutt, here’s a classic by French futboller Zidane on Italian defender Materazzi during the 2006 World Cup.

At this time the joker grabbed me around the neck and started trying to choke me. I remember giggling because he could not get his little hands around my neck to apply very much pressure. I had a quick look around and backed myself against a wall while the criminal was still attached to my neck. I then was forced to head butt him twice to the bridge of his nose as he was falling, I put both jackets in one hand and took off through the crowd out of the bar. RJMDL was waiting outside, I told him what had happened and we decided to have a quick look for you and then get out of Dodge. We could not find you so we left for the safety of where we were staying. So I really don't think I was a thug just a bit of self defence. I also remember the girl who spoke to me had a look of shock on her face, I don't think she was expecting that ending.”

Head-butting drunk Basque dudes in the middle of a raging drunk fiesta in the alleys of a town immortalized for screaming violence and death is not a good way to stay healthy. That’s why they abandoned me. Oh well.

“Fair cop” as they say in Britain and the provinces.

The party scene in the town of Guernica, as depicted by Pablo Picasso.

If in this life I have been an hombre correcto from the womb to the tomb and lived righteously, when I get to the Pearly Gates and Saint Peter looks through his Golden Book and holds up his hand and says: “You’ve been a proper lad, I’ll grant you three wishes.” Well I know what I will answer.

One of those wishes will be to go back to Santa Cruz and be a surfer in the 1970s, the second will be to do anything as well as John Bonham plays drums but another one will be to have the skills of Tom Carroll in his prime at foffing eight-foot Mundaka.

Because… wow! This is a beautiful wave in a beautiful place. A wave designed by a loving God who loves surfers, who loves goofy foots, who loves surfers who like to go fast and get sooo pitted. But don’t want to have to paddle.

The setup is ridiculous. If you’re stumbling into the water half-drunk and tired, you slip and slide carefully down a moss-covered boat ramp into the cold waters of a stoney old harbor that was built originally for fishing but now is almost entirely pleasure boats. Paddle about 300 feet through the harbor entrance where you most likely will see glimpses of someone getting pitted, sooooo pitted! and that speeds you up through the two jetties and turn left into a tight little channel that never seems to close out.

Mundaka will go to 12 feet and even bigger but you can almost always slip through that channel as the wave spits and growls at you like a T Rex behind a high electronic fence.

Craig Sage has seen it all after 40 years of living in Mundaka. When asked what’s the biggest he’s seen it, he responds: “Rideable probably 15 feet. Not rideable?! Well I saw a wave that broke behind the harbour wall in Bermeo a few years back: The harbour wall is over 30 feet high and the wave continued to rumble into Mundaka. It came up so much quicker than expected and had one local surfer thankfully rescued before that wave broke.”

Craig reckons the ideal conditions are 4 to 6 feet, on a spring tide with those offshores howling clean and cold out of the south down the river through the valley. “The wave actually hugs the bank much better at that size and the barrel is more precise.”

Paddle through the harbor and out the jetties and through that narrow channel and out the back to the top.

And there you sit, waiting for a bomb and when a bomb comes, that’s when you want to be Tom Carroll. The need for speed, because this wave is all about down the line speed. Mundaka breaks hard and fast and hollow along a solid sandbar that disappeared for a while from 2003 to 2005 but then reappeared, thank Odin.

Dinner fiesta in Mundaka, circa November 1983. Your Humble Narrator is lower left. Bertrand is two up, then Duncan. Alto Bill Kaz is the tall chap smiling at the camera. Next to him is Craig Sage and the handsome dude with the moustache is Blindforce Leftenant Jeff Sheard. Not sure who the other chaps are or what we were celebrating, perhaps your Humble Narrator’s best and only dry barrel. Or maybe just celebrating being surfers and young and in Europe in 1983 - before surf cameras and the Internet and all that. Photo: Steve Vallance/Blindforce.

According to Google Earth, the wave at Mundaka is around 1300 feet long. For comparison, Kelly’s wave in Lemoore is around 2200 feet and it’s 2900 feet from the Malibu Colony fence at Third Point to the base of the Pier. Rincon is about 2000 feet from the top to the highway.

It’s about 1300 feet from Sewer Peak to the O’Neill House at Insides, so there you go: Imagine taking off on a frothing eight feet of Atlantic energy at Sewer Peak and then turning and burning and weaving in and out of the barrel all the way to Jack’s house.

Red blob in the north Atlantic, Mundaka surfers get frantic. This dream monster blob in February of 2021 created a couple days of giant surf from Mullaghmore to Mundaka to Nazare and probably all-time Morocco. For the whole story clique aqui:

That’s Mundaka. A stupidly great wave when it’s all coming together: Lashings of raw Atlantic energy, organized over a perfect sandbar with offshore winds usually blasting in from Guernica and beyond.

It’s 2000 miles from Mundaka to the southern tip of Greenland and in between there, those Atlantic storms move toward Ireland and kick up a great deal of energy that is all-powerful but evened out and lined up by the time it bends into the Bay of Biscay and trips over the sandbar at Mundaka.

This is a powerful wave. Get caught inside there on a big day or eat it in the barrel and find out. And it’s also consistent when it’s really pumping. The sandbar is part of the Urdaibai estuary which empties and fills with the tides.

The tidal range at Mundaka is as much as 15 feet plus, which is pretty much double California. When the tide is high the wave pretty much disappears except for the biggest days. And when the tide is going out, it goes out like that current under the Golden Gate Bridge and along Ocean Beach.

There is a fuerte current that you have to paddle against to stay in position at the top. A lot of paddling at the top, but not so much to get back to the top.

But the real gem of this wave comes after kicking out. And most people kick out before the wave is really over and dumps on the beach at the other side of the bay.

Instead of paddling back out staying wide right of all that energy watching other dudes get barreled, the path of the righteous man is to ride the white water toward the village and usually end up in a river/tidal/ocean little eddy behind the Iglesia de Santa Maria. All that outgoing tide and the river current cut a permanent channel between the town and the sandbar, and that creates a kind of aquaticscalator that the smart surfer can hook into and get taken straight out the back - no paddling needed really, other than steering.

Catch a bomb, go Mach One for a quarter mile, get barreled three or four times, then ride a water escalator back to the top, looking up at cliffs lined with cheering, partying Basque folks and lashings of pretty girls.

(There are a surprising number of blonde Basque girls and some historians attribute that to the Vikings showing up in the Mundaka area as far back as 900 AD, and also some Saxons. Whatever, there’s a lot of pretty girls: blonde, brunette and Celtic red.)

Ridiculous, truly. The whole scene.

When all this was happening in 1984, Craig Sage had been in Mundaka off and on since 1980: “The second time I was returning on my way home to continue with my University studies in 1982 but never made it back to Australia.”

Sage fell in love with the wave and also a lovely Basque gal, Itziar. They married in 1985 and Craig put down roots. He opened the Mundaka Surf Shop in 1984 but officially in 1985: “This year I celebrate 40 years of living and surfing in Mundaka!” Sage said exuberantly.

There has been a lot of water in and out of the estuary since then: “I would love to be 25 again with the equipment of today and do it all again,” Sage said in 2022. “In the early days South African surfer Marc Paarman showed us the first Thruster designed by Lisle Coney. Paarman showed we actually could surf from the peak as the bottom turn was able to match the speed. On single fins we struggled to beat the lip. This forced us to surf more down the line.”

Among the extranjeros who surfed Mundaka well, Sage tips his sombrero to fellow Aussies: “Gary Elkerton pulled off ridiculous backhand arcs straight at the lip and his partner in crime Robbie Page. Margo in late 80´s with his no grab stand up barrels. Barton Lynch who come for a surf and stayed 10 days: elegant. Maurice Cole who challenged me to get out on the bigger days - just the two of us - some scary moments but a full-on adrenalin rush.”

Craig Sage in the barrel on the cover of Mundaka: Surf to Live. The book on Mundaka history he published in English, Spanish and Euskara.Available on Amazon.

As for the local rogues: “In the early days the Fernandez and Acero brothers, Aritz Aramburu, Iker Fuentes, Natxo Gonzalez and a heap of the new surfers whose names I have no idea but tear this wave up from four feet to 15 feet.”

At six in the morning I got off the train, and straight into the surf on a borrowed board - with a hangover and no sleep. I blew every wave for the first hour. Then I stood up on a medium-sized insider.

I got to my feet shakily, and barely made it to the bottom. I came off the bottom off balance and in big trouble. I am only capable of standing in a half crouch, but that was all I needed. The wave threw out oily smooth over my head (Glatt smooth, if you’re Kosher). I heard that roar, and saw the wave funnel down and turn the corner. A Frenchman paddling out was peering into the tube and hooting. I shot out of the tube and fell off, wasting 200 more yards and the inside bowl.

This isn’t me. I was deeper, probably. This is local lad Kepa Acero doing what everyone should do at Mundaka - get barreled. Photo from online.

Oscar was paddling out and trying not to smile. He rewarded me with the ultimate Australian superlative: “That was bullshit,” said Oscar, trying not to look proud that he was traveling with such a hot Seppo surfer.

(One of the things I was mocked for was my cowboy California western Spicoli meathead drawl. Oscar claims I came out, fell off right in front of him and said, “Duuuuuuuuuude!!!! Did I just get tuuuuuuubed??!?!?!?” But I was a little shocked. That was the real deal. Pitted, bro, so pitted!!! Way.)

I was touched, but blew the rest of my waves, crawled home and slept until sunset. That night in the pub the impossible happened again: An Australian gave a compliment to a Seppo.

“Aw, you got a classy barrel today, mate,” said the Australian from the Green Slime (his lime-colored Volkswagen Bus).

Yep. I shouted everyone a beer, and decided to stick around.

“Your best tube ride?

I got one at Mundaka in Spain that was pretty crazy. I think I was in the barrel for about fifteen seconds and halfway through I had to grab my rail and I let go because I thought I was going to eat it. And I went at least as far again, and it felt like I was underneath the waterfall because the lip never changed where it was in relation to how deep I was, but it keep on chandeliering. Like when you’re standing in a waterfall and little chandeliers of water are splashing around randomly. The wave didn’t change shape but these little bits of water were falling through because the wind was kind of onshore but it was sucking off the sandbar so hard that the main shape of the wave was perfect, but there was always whitewater falling in just lightly, and I was just passing through it, and it just kept feeling like any second I was going to fall.

So I let go of the rail and I just stood there going, “I’m going to fall. I’m going to fall. I’m going to fall. I’m going to fall. I’m not going to fall.” It felt like I said that to myself like thirty times before I fell. And when I came up, I just popped straight up and looked back and it was just an incredible ride. These things stick in your brain forever.

”

Three potheads, wasting away in the Otra Bar: Chris, Ben and RJMDPL - the Mauritian. Photo: ???

The surf went flat and stayed flat. Oscar and Felix headed south, looking for waves to surf and drunken locals to head-butt. I was supposed to go with them, but I dissolved our week-old partnership.

“You wouldn’t read about a guy like that,” said Felix. “Seppo bails out on us already!”

I wanted to surf the fishing village some more, and the Australian Odd Couple were impossible to live with.

While the majority left for places north and south, I settled into the fishing village with a dozen other internationals. We were gambling that a sudden swell would leave the Point full of waves and empty of people. Hog heaven.

(This was 1984 mind you. Long before they could predict a swell immediately after a polar bear farted in the Arctic. We didn’t really know what was coming, and that was kind of cool, in a way.)

A lovely wave from any angle: Land, sea or air. But nicest from inside. Photo from the Internet.

Well they work pretty well. Photo stolen from magicseaweed.com

When the surf went flat there was little to do in the fishing village, but the town had a hypnotic effect on certain people. There was little to do, but we never got tired of not doing it.

We watched the soccer… sorry, futbol highlights on one of the two television channels. We drank countless mugs of cafe con leche. For laughs, we ordered Fockink Gin by name. We listened to the shark and war stories that all South Africans have. We watched the weather maps for low pressure systems. Two hundred Marines died in Lebanon on October 23, 1983, and we read about the aftermath of that.

We got sick. To justify the risk of waiting, we watched Super-8 movies of perfect point waves at the Otra Bar. We recorded lewd songs and played them on the stereo in the bars. We read old surf magazines. We sat in the sun on the benches that overlooked the Point and watched for a sign, a ripple. Nothing for two weeks.

We played pelota - a ballgame played with wooden paddles. Every town in the province had a Catholic church, and every church provided a wall for pelota.

“Inside for the mind, outside for the body” is how the church saw it.

As the flat spell continued, many of the internationals became very good pelota players. None better than a swarthy Frenchman from Marseilles, Bertrand, who looked and spoke exactly like Inspector Clouseau. Americans who met him for the first time would burst out laughing when he said “Hello.” He had never seen a Pink Panther movie, and didn’t understand.

Also at the time, the song Ca Plan Pour Moi was very popular. Sung by a French pop star named Plastique Bertrand. I still hear that song and it reminds me of those Mundaka days.

Also, Bertrand looked like Les Freres Dalton - the Dalton Brothers - the bad guys in a very popular French comic book series call Lucky Luke.

Lucky Luke arresting Les Freres Dalton.

So depending on how stoned/drunk/sarcastic we were, we called him “Inspector” or “Plastique!” or “Joe Dalton.”

Bertrand didn’t like any of it. “Awww fuck off you guys” he would mutter through lids slitted by mass quantities of hashish.”

I felt sorry for Bertrand, until I challenged him at pelota.

Bertrand was due to enter the French Army for his mandatory service. He was in the fishing village surfing, getting blasted on legal hash, and blasting anyone who dared challenge him at pelota.

Voici le Inspector Bertrand Dalton! In all his glory, partying next to an English lord who was later sent to Newgate for robbing coaches. Photo: Steve Vallance/Blindfore.

Bertrand was an amazing pelota player. This became important toward the second week of the flat spell. The internationals took out their pent-up surf energy on the walls of the church. Bertrand would take on the two best players in town and beat them single-handed.

Clouseau. Skulking and spying.

The pelota court was within 10 yards of the cliff that overlooked the Point. We never let the ocean out of our sight. We were ready for action. We weren’t getting it.

The fishing village overlooked a wide bay rimmed by mountains and capped by an island. The view from the cliffs over the bay could cure leprosy.

The internationals weren’t the only ones who were entranced by the peace and ease of the town. Bilbao is the largest city close to Mundaka, about 17 miles as Google Earth flies: “There is a fine road to Bilbao from anywhere along the Basque coast.” Hemingway wrote in Death in the Afternoon. He had a love/hate with the big, grimy, industrial Basque city: “Bilbao is a rich, ugly, mining city where it gets as hot as St. Louis, either St. Louis, Missouri, or St. Louis, Senegal, and where they love bulls and dislike bullfighters.”

Bilbao has improved since Hemingway’s time, but it’s still a wealthy, grimy industrial city. Photo from the Internet.

All true, and especially when we were there, as Bilbao was hit by “inundaciones” which covered the grimy city in a layer of mud. The citizens of Bilbao and the inland Basque towns and cities escaped the grime and dirty air of industrial cities to breathe the salt air and stroll about the town. The citizens watched the placid ocean as intently as the internationals, but for different reasons.

The surfistas extranjeros added to the mystique of the town. When the surf was cracking, the citizens would line the cliffs to watch the show. Paddling out, you knew how a matador felt in the ring.

The influx of people on the weekends gave the small town a raging nightlife. Local girls would come from all around to mingle with the rubios. This arrangement worked well for everyone.

Basque girls - always ready to dance and party.

The local girls had the jet-black hair and flashing eyes for which the women of their country are famous, but the girls in the area had something extra. It’s hard to explain; they were a mysterious bunch. They had a bemused, sensuous reserve that was like the smile on the Mona Lisa. They loved to drink, dance and talk until well past the witching hour.

WE WERE SURFERS ONCE… AND YOUNG

A Slideshow of Images from Blindforce Captain Steve Vallance.

The custom on the weekends was to eat dinner very late in the evening. The local girls would leave their houses ready to party, when many Anglos were ready to call it a night. The only weekend night we went to sleep before four in the morning was Christmas Eve. It fell on a Saturday, which ruined it.

“You wouldn't read about it,” grumbled Alto Bill, who let a recurrence of malaria spoil his Christmas cheer.

Just as the Catholic church was the dominant building in the fishing village, so was The Church the dominant structure in the mores and manners of the girls.

“Inside for the mind, inside for the body,” was how the frustrated internationals saw it.

It may not have been solely because of religion, but the girls in this province and town were (in)famous for their unwillingness to screw around.

“No shagging!” as The Englishmen said it, and you have to marvel at how the English can poeticize the most vulgar expressions.

Las chicas vascas knew that we knew what the score was. They knew we didn’t like it, but we learned to. After that the internationals and the local girls mixed well, and had a hell of a good time together.

Many of the local girls were shy or coy or disinterested. The Englishman came up with nicknames for the girls whose names we didn’t know, or couldn’t pronounce: “The Girl From the Flat,” “Motorcycle Suzie,” “The Hash Queen,” “Filthy Barrel,” “The Translator.”

Mundaka in all its glory - a beautiful, powerful wave in a beautful, powerful setting. Kelly Slater said the longest barrel he ever got was here. Imagine that, after all the waves he’s ridden around the world. Photo: On Line.

I fell for “The Bootmakers Daughter.” I suppose I’m a romantic. Why else would I be enjoying perfect surf and easy continental living while the rest of the United States was at home earning their MBA’s? The girl I fell for lived in a house along the main street of the fishing village. Her father worked in a shoe shop below the house. The Bootmaker’s Daughter was tall, gorgeous and very dignified - regal in a way. Untouchable. Many of the internationals had taken a run at her and been stonewalled. She must have thought I was harmless - an hombre correcto - as we became good friends on the first night we met. Almost made an enemy out of Doug Wombat because of that.

On weekdays, the Bootmaker’s Daughter taught kindergarten at another fishing village up the coast. On a Saturday night, one week into the flat spell, the Bootmaker’s Daughter invited me to accompany the Translator to visit her during the week. She had seen me playing with some of the schoolkids in the fishing village, and guessed correctly that I like rugrats. The plan was for me to attend her classes, spend the night at her apartment, and return to the fishing village the next day.

Well, why not? I wanted to go. But I knew that if I left, the surf would come up. Guaranteed. I KNEW this would happen. That’s the way my luck goes sometimes. Visiting the Bootmaker’s Daughter was a unique opportunity, but a potentially disastrous decision.

I studied the ocean and debated the decision for three days. I unwisely leaked word of my dilemma to the internationals who were becoming increasingly tense from the lack of surf. They urged me to go. They were all seasoned travelers who’d been burned making similarly stupid decisions.

“I don’t care what you do, as long as the surf comes up,” said The South African Who Had the Place Wired.

“Go for it, mate. It’s only for a day -- you won’t miss anything,” lied the Australians. Serge and Eddie were mates who’d just returned from South Africa. They had each other’s names. Eddie was usually surging, while Serge was lethargic.

The Englishman shook his head. “If you go, you’ll blow it. But I know you’ll go because you’re stupid, and the Bootmaker’s Daughter is beautiful.”

The Inspector said, through hash-lidded eyes, ‘Don’t go for a cheek! You’ll miss ze vaves! Plenty of cheeks. No vaves for dayz!” He looked at the flat ocean. “Pelota, anyone?”

Never turn your back on the ocean. It can work you over without getting you wet. I knew I was risking a supernatural pummeling by leaving town during a flat spell. I also knew that if I stayed, the ocean would stay flat. If I left, the surf would come up. The ocean demanded a sacrifice. It works that way.

The day came when I had to make my decision. We had to telephone the Bootmaker’s Daughter that evening to tell her whether or not we’d arrive the next day. I watched the ocean nervously from dawn to dusk. Nothing. I looked at the weather maps. Nothing. I watched the weather news. Nothing. I asked the fishermen. No way the swell would come up that fast.

I showed myself to be a heel - something less than an hombre correcto - by laying my priorities bare to the girls.

“Olas grandes, amigas,” I explained. “No quiero perdir las olas.” The girls shook their heads, but they understood. Prioridades. Surfistas locos. Americanos.

It wasn’t very gallant of me, but anyone who has traveled 6,000 miles to surf knows how important a day of good waves becomes. You don’t want to risk missing a good day, because you might not get another. I wanted to visit the Bootmaker’s Daughter. I had left the town twice during the flat spell and had returned to find I’d missed nothing. I wanted to go, but I had a bad feeling about this time.

(In fact, one time I actually left Mundaka to travel to Madrid to see a fricking museum!

An art museum! Fag!

Triptych for Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights on display at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. The very odd, beautiful, scary painting was created 10 years either side of 1500 and it measures 7′ 3″ x 12′ 9″ And it makes an observer wonder: “What was that dude smoking?” Photo from the Internet.

I wanted to visit the Prado and see the full-size Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights triptych and Picasso’s Guernica. I could never say that to The Internationals or the Basque girls or forever be stained as a poofter, a nob, a wanker, andouille, moegoe, an hombre dilletanto.

As I was leaving some of the Basque girls asked why I was going to Madrid.

I said, jokingly: “To spit on Franco’s grave.”

They lit up and said, “That’s what we do!”

I was joking, they weren’t but they had every right to an ancestral dislike of Franco. Just as Ukrainians will always have an ancestral hatred of Putin. And proper-thinking Californians will always have an ancestral dislike of Trump.)

At 8:00 PM I looked at the ocean one last time. Not a ripple. Flat. A nice sunset, but no surf. I walked to the phone booth and made my decision. I was committed. We finished the call to the Bootmaker’s Daughter, and the Translator walked home shaking her head. I walked to the pub to tell the internationals what I had done.

They gave me three cheers, and we all walked to the Atalaya to watch the swell jump.

The author, page right, walking along the Atalaya at Mundaka, some time during the fall/winter of 1983/1984. Photo: Darrell Jones in Surfer Magazine.

And it jumped! You had to see it to believe it. The tide was low at 10:00 PM, so I walked down with The Englishman. The surf was pumping. The wind was blowing fast through the river valley, and straight offshore. There was enough light to see whitewater folding over and bouncing for hundreds of yards down the line. It was perfect.

A hardcore surfer would have bailed out on the commitment. I figured that if I stayed to surf I would cause a hurricane, or onshores, at least. After checking the surf early in the morning and seeing tons of lonely swell, I boarded the bus with the Translator and headed north.

Two hours later I got another look at the Point, as the bus traveled north along the other side of the bay. I saw less than a dozen black dots riding more than a dozen 6’ waves.

“You wouldn’t read about it,” I muttered to myself.

“¿Que quieres a leer?” asked the Translator.

“Nada,” I said, “No te preocupa,” as the bus turned the corner and headed for the other fishing village.

A scene along the Basque Coast. This is San Sebastian - a beautiful coastal city popular with anyone whose been there. And it has surf. Photo from the Internet.

The Basque coast of Spain is beautiful and green and blue and Big Sur-like but also foreign and definitely somewhere else. The people and the way they lived made me think of The Hobbit, with a soundtrack by Led Zeppelin. The Basques are Hobbit-like: Ancient and strong, living close to the land in earthy huts and houses that seemed to be emerging from solid rock and green pastures.

I went to Spain with my high school Spanish, but the girls teased me: “Hablas como un Mejicano,” they teased.

But I knew enough to answer in lithpy Cathtilian: “Pido dithculpath, thenoritaths, por mi ethpañol mexicano. ¿Eth ethto mejor?”

When the girls got wise we could kinda understand their gossipy strategizing and analysis in Spanish, they switched to Basque, and all was lost. Basque is an entirely different and very ancient language.

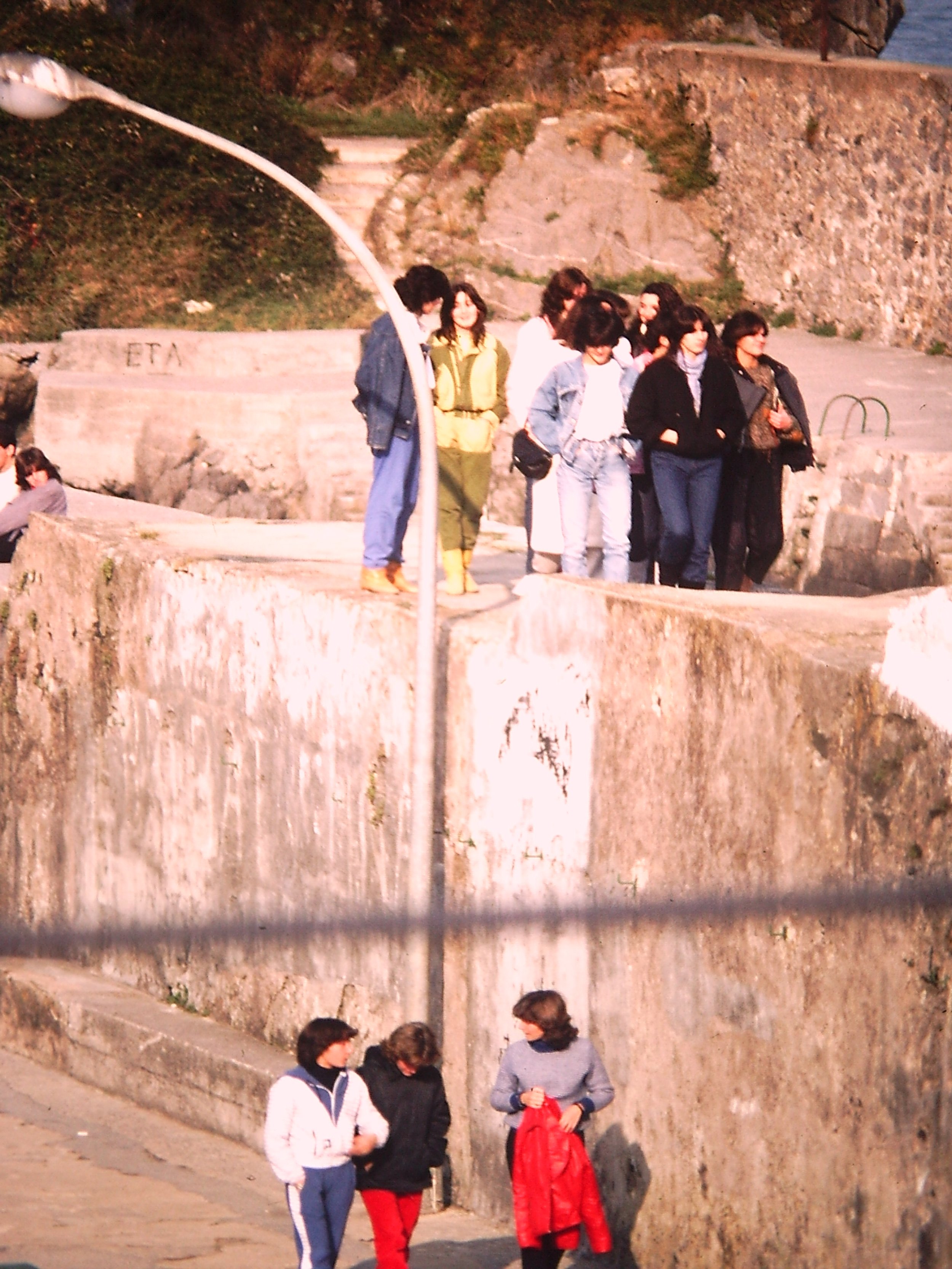

Basque graffiti. If it looks violent, it is violent. The Basques are kind of like the Northern Irish of Belfast and the Catalonians. They want their independence and aren’t afraid to fight for it.

Riding through small towns on the school bus with the Translator, the graffiti was in Basque, and foreign, mystical - like Elvish runes. The Translator translated pieces as we moved along. “Presoak kalera” had nothing to do with laundry. It means: “Let the prisoners out!” Referring to the ongoing, deadly conflict between the Basque people and the Spanish Guardia Civil.

Serge and Eddie ordered me to keep my eyes peeled for surf. I didn’t see any, but I saw a lot.

As the bus rolled along through small towns and fishing villages on an absolutely perfect, beautiful blue winter day, the soundtrack in my head was also mystical and Hobbitish as interpreted by Led Zeppelin: Ramble On, Misty Mountain Hop, Battle of Evermore.

And when we got to the other fishing village: Dancing Days.

The Bootmaker’s Daughter had control of a roomful of brown-eyed kids who worshipped her. The kids considered it a great novelty to have a tall, antic rubio in the classroom. I managed to disrupt an entire day’s instruction. That’s always worth doing.

Squid cooked in its own ink. Looks good. Is good.

The girls shouted me lunch at a small restaurant near the harbor. The girls ordered for me. I trusted them and my trust got me a bowl of black goo with bits of raw squid swimming in it. Calamari con tinta - squid in its own ink.

I like calamari, but I liked it cooked. I don’t like eating substances that have the color and consistency of crude oil. Neither did the Translator, so I wasn’t too embarrassed.

That evening we sat in a cafe near the harbor, drank coffee and talked. The girls cooked dinner.

That night in a separate room from the Bootmaker’s Daughter. You wouldn’t read about that. But I wasn’t as aggravated about missing the surf. I’d had a fun day, and tomorrow is another day.

The next morning, we rushed back to the fishing village. There was still some swell left, but it was clear - it was made VERY clear - that I’d missed a CLASSIC day. The internationals had that look of fatigued satisfaction. I knew they weren’t exaggerating as they raved about the waves I’d missed.

Looks like a fantasy lineup you’d draw in a schoolbook, but it’s the real deal: a really really good wave. Long and strong and down to get the friction on. Photo from the Internet.

Watching performances by The South African Who Had The Place Wired was almost as much fun as surfing the Point and I had missed one of his exceptional displays of tube-riding. The Internationals were yakking about it for months.

As The Internationals ridiculed me for missing the surf, they were also aware that I had spent the night with The Bootmaker’s Daughter. As they laughed at me, they searched my expression for a clue as to what had happened the previous night. I let them see nothing - I had to save face.

So, I missed one day of perfect waves. It could have been disastrous, but it turned out that my five months in Europe were full of waves. I was lucky to catch one of the best seasons in years.

In France we hung out with Miki Dora and I wish I’d known then what I know now because I would have asked him a lot about Malibu in the 50s and 60s and other things.

Trunk It: A montage of moving images and music for the Surfing Heritage Foundation: Surfing and hula and Duke in Waikiki from 1906 to World War II and then John Larronde’s Sweet Sixteen movies of California surfing at Sano, Malibu, Rincon and Ventura Overhead circa 1947. Worth a look and a listen: Ellington to Elvis.

I wish I could have shown Dora Trunk It before he died. I woulda made Da Cat cry: Visions of Malibu in 1947 featuring his style mentor, Matt Kivlin. Dora probably thought Malibu would always be this way. It wasn’t and that among other things spun him out.

In Portugal with another Aussie crew who called themselves Blindforce, we stumbled into Nazare on a dark and stormy day. A sight that made us doubt our eyes took us out to that now famous point, to see the Atlantic Ocean in full roar - many decades before Nazare became famous.

I wish I had the Super 8 we shot of that day from that little alcove at the bottom of the stairs.

Working at SURFER Magazine for 10 years I always said “The biggest waves I’ve ever seen were at Nazare.” And then Garrett Mcnamara and Maya Gabeira and friends proved me right.

France to Spain to Portugal, back to the fishing village for Christmas, then across the top of Spain through Pamplona to Barcelona.

(Pamplona was cold and beautiful and empty in the middle of winter. Echoes of the running of the bulls and lots of violent photos on the walls. I walked the ramparts of the city and looked into the Pyrenees and the music I heard was Carmen.

On the bus from Pamplona to Barcelona, there were no more seats so I sat in a chair surrounded by bemused Spanish women. There was a movie playing on the bus, featuring Jill Clayburgh which had a scene with a wedding rehearsal. The Spanish women couldn’t BELIEVE there was a culture that had to rehearse weddings.

They asked me many times over if that was how Americans did it. I said it was.)

In Barcelona I visited the Gaudi Temple and saw a shooting range where they actually blew away captured, live pigeons. I doubt that’s the go anymore.

For New Years we celebrated Nochevieja by eating grapes and I had another Lost In Translation episode. I had been going back and forth between France and Spain and getting my “ques” and “en” and “de” mixed up. I would say something to the Catalan girls in what I thought was Spanish but would mix in some French.

They would look at me admiringly and say, “Ho has dit en català perfecte? = “You said that in perfect Catalan.”

Then along the Mediterranean Coast to Nice, where I caught a train back to Paris and flew home.

All of this before cell phones and the Internet, when the world was still mysterious and we didn’t know where we were going, or what was coming.

And in some ways, that was more fun.

I got so many days of good waves in France, Spain and Portugal, they all blend together.

One of the days that stands out, however, was the one I spent with the Bootmaker’s Daughter at the other fishing village, trying to forget about the surf long enough to enjoy myself.

At the time, I was in pain. I knew how a Volcano Virgin feels on the eve of the plunge. I had made myself the laughing stock of the internationals by setting myself up to miss a day of waves. They thanked me for being the sacrifice.

Surf martyrdom sucks.

Thank you for reading about it.

WHO THEY WERE AND WHERE ARE THEY NOW

THE BOOTMAKER’S DAUGHTER = BEGONA URQUIZA GAUBEKA

Begona - aka The Bootmaker’s Daughter - photographed surreptitiously by Craig Sage circa 2017.

When You Wouldn’t Read About It came out in SURFER Magazine in 1984, Craig Sage said he showed it to Begona (aka The Bootmaker’s Daughter) and it “Put a smile on her dial.”

Many years later, while helping Craig edit a book on Mundaka in English, Spanish and Basque, he sent this photo of T.B.D with an explanation: “Have not forgotten about you!!!! Here is a foto of Begoña that I had to take quickly as she refused to have a foto taken with her family, ( They have a son pretty tall 1.90 approx. Sorry I could not get a better or up close one.”

Wish I had a photo of her in 1984. She was ridiculously pretty.

THE TRANSLATOR = MARY LOUISA PERTIKA, OR THE OTHER ONE?

THE AUSTRALIAN ODD COUPLE = CHRIS ROSS AND RONALD JEAN MARC LOUIS

Chris Ross is happily married to the charming and glamorous Miss Kristie. He works for the fire brigade in Maroubra and has three sturdy kids, ????, ??? and ??? who are really good at head-butting.

THE ENGLISHMAN = DUNCAN NORRIS

Duncan on the right, standing on the roof of SURFER Dog with a bunch of local rogues. Photo: Ben I think.

Duncan Norris came to California and worked with me in my Surfer Dog hot dog wagon in the 1980s. He worked as a flight attendant for American Airlines for many years. He too is happily married to the charming and glamorous former Miss Kathy Jones and they have two lovely daughters, Holly and Gemma.

ALTO BILL = BILL KACZMAREK

Bill Kaz survived Mundaka and malaria and continued to have adventures around the world, including working with Martin Daly on The Indies Trader. Bill married the charming and glamorous Tracy and now they have three (?) offspring.

This photo appears to be the entire Kaczmarek clan in front of what appears to be the fancy Guggenheim museum in Bilbao?

THE INSPECTOR = BERTRAND ????

Would love to find out Bertrand’s last name and send this to him so he could say, once again: “Aw fuque you guys!”

Reunited and it feels so good. Steve Vallance and Bertrand at JBay circa 1998. Photo: Steve Vallance/Blindforce.

Sixteen years after Mundaka, Steve Vallance was surfing Jeffrey’s Bay: “I’ve also got a few of The Inspector somewhere from a trip to South Africa many years after Mundaka… Having made it in myself I spotted a bloke obviously struggling to find the keyhole for a safe exit from massive J-Bay and after guiding him in fell over laughing: That unforgettable smile, the accent, the theme from The Pink Panther running through my head – it was none other than Bertrand – ya just wouldn’t read about it! We had a great time with plenty of reminiscing over the Mundaka sessions.”

THE SOUTH AFRICAN WHO HAD THE PLACE WIRED = MARK PAARMAN

DOUG WOMBAT = DOUG DALLY

“Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.”